Housing

“Negro Co-Ed Says Other Tenants Caused Ouster”

“Jewess, Denied Room, Sues”

“University Club Ousts Colored Grad Student”

The headlines varied but the message was clear.

Housing discrimination was rampant in Madison in the mid–20th century. Jewish students, African American students, and international students found closed doors, both literally and figuratively, as they searched for housing.

The problem was twofold. First, UW–Madison had not yet built a robust dormitory system. Instead, it kept a list of approved private landlords from whom students were permitted to rent housing off campus. Second, private landlords in Madison expressed racist and antisemitic beliefs, and prior to the Fair Housing Act of 1968 they were legally allowed to discriminate.

Housing Denied

Mildred Gordon

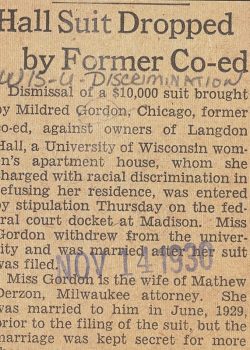

In September 1929, Mildred Gordon, a Jewish woman, arrived at the private Langdon Hall dormitory. She was excited at the prospect of living in a newly constructed building close to campus. She even created custom stationery with her new address. But upon her arrival, her landlord informed her that there was no longer a room for her. A gentile, a non-Jewish person, had taken her place. Gordon “considered it an insult” and sued the dormitory owners for breach of contract. Eventually, she received an undisclosed settlement from the management company.

Many Jewish women at the time faced similar experiences. Antisemitic discrimination was so commonplace that private dormitories specifically for Jewish women were created in response. This allowed Jewish women to find community with one another while avoiding the problem of housing discrimination. Some of these dormitories are still in operation today.

Tremetria Birth

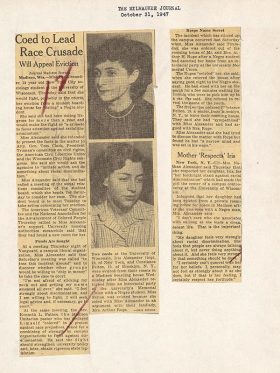

In 1940, Tremetria Birth, a Black graduate student in the English department, was evicted from her rooming house after her landlord stated, “I don’t believe that colored and white people should mix, especially on State Street.” Although she did not choose the spotlight, Birth did not hesitate to speak out about discrimination in the city. At a town meeting, she stated, “The U.S. sits back smugly and condemns fascism but practices the worst kind of discrimination at home.”

Arthur Burke

In October 1944, graduate student Arthur Burke arrived at the University Club and moved into his room. He was set to spend the next year on the Adams Fellowship teaching as a graduate assistant in the English department. The next day the University Club asked him to leave because of “strong sentiment among club members against negro residents.” Burke was offered alternative residence at the YMCA but rejected it, calling it “an affront to have offered and craven to accept.” Burke immediately told history professor Merle Curti of the eviction. Outraged, Curti partnered with Helen C. White, an English professor, and Paul Clark, a professor of medical microbiology, as well as student organizations. A coalition of 185 students lobbied the University Club to end its discrimination policy. The group’s advocacy, combined with Burke’s principled stand, eventually forced the University Club to hold a referendum. The majority voted to end racial discrimination at the club.

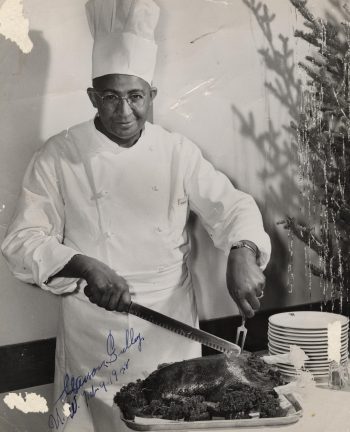

Chef Carson Gulley

Housing discrimination in the city also affected UW–Madison faculty and staff. Famed campus chef Carson Gulley almost left the university in 1930—only four years after he arrived—because he and his wife were struggling to find housing. The director of dormitories, Donald Halverson, built a small apartment for the couple in the basement of the Tripp Hall dormitory. While this measure helped them in the short term, when Gulley left UW–Madison in 1954 after being denied multiple promotions, he and his wife once again struggled to secure housing in Madison.

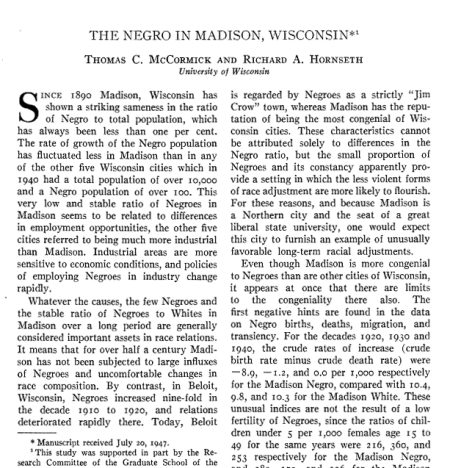

“The Negro In Madison”

In 1947, the findings of a three-year study into the “situation of Negros in Madison” were published in the October edition of the American Sociological Review. They were striking and provided a glimpse into the lives of the small population of Black residents in Madison, including those who may have been students, faculty, or staff at the university. The findings noted that although Madison had a reputation of being “the most congenial of Wisconsin cities,” there existed a rapid turnover of Black residents. The low ratio, the study found, was caused by limited employment opportunities and the inability to find housing, noting, “It can be shown that housing and jobs available to Negros in Madison continue to be very inferior to those available to whites.”

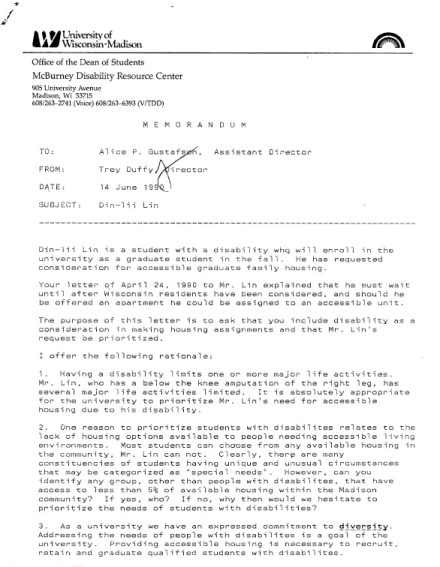

Din-Lii Lin

Students with disabilities also struggled to secure accessible housing on and off campus. In 1990, Din-Lii Lin, an international graduate student with a disability, applied for student family housing in Eagle Heights. Because he was not a Wisconsin resident, he was placed on a waiting list. University Housing did not factor in disability when determining housing priority. The director of the McBurney Disability Resource Center, Trey Duffy, advocated for Lin, arguing that disability should be taken into consideration. Duffy pointed out that Eagle Heights, which had more than 1,000 units, included only two accessible units, even though federal regulations called for 5 percent of housing to be accessible. On June 16, 1990, Duffy wrote to Lin, “I regret to inform you I have been unsuccessful in my request to University Housing. … I am ashamed and embarrassed.”

Read the official correspondence between Din-Lii Lin, Trey Duffy, and Alice Gustafson (PDF).

Housing Discrimination and International Students

International students also struggled to obtain housing in Madison. In 1964, the Madison Campus Foreign Student Program released a preliminary report to the Board of Regents based on a survey of 961 foreign students. It found 59 percent of Black students said they encountered discrimination. The report also noted that Chinese, Indian, and Pakistani students faced discrimination.

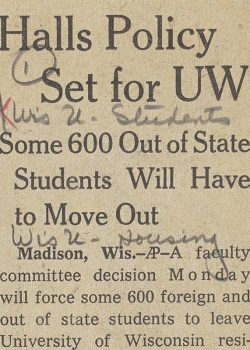

International students also struggled to gain access to university-operated dormitories. A Wisconsin state law mandated that the university give preferential treatment to in-state students when filling dormitories. When in-state students did not fill up campus-owned and -operated dormitories in 1960, the faculty voted to open the dormitories to out-of-state students, including international students. But by February 1961, when in-state students requested dormitory access in higher numbers, the faculty voted to remove out-of-state students. The Wisconsin State Journal did not mince words when it described the vote: “A faculty committee decided to force 600 foreign and out of state students to leave University of Wisconsin residence halls next year and find housing in private homes.” The faculty vowed to “make every effort” to help these students find housing but most were forced to find private housing. While the policy was implemented to support Wisconsin students, in its practice it punished students of color and Jewish students, most of whom were not in-state residents due to the overwhelmingly white and Christian population of the state.

Wendolyn Bell

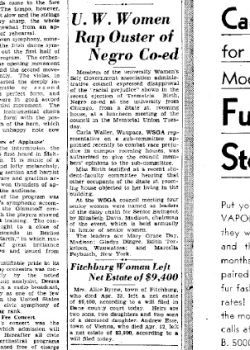

Wendolyn Bell was notified of a vacancy at the College Club, a university-approved women’s rooming house. When she arrived, Mrs. Elsie Moore, the housemother, informed her that she couldn’t have the room because she was “colored.” Moore said she “would have never guessed [Bell] was a Negro” from the handwriting on the application. While the Student Board and the AAUW (American Association of University Women) came forward to support Bell, the rooming house was not removed from university-approved listings. A student opinion article on the issue did not mince words: “The university should not disseminate highfalutin academic theories on quality and justice on one hand, while they give the go ahead sign to prejudiced individuals and organizations. This is hypocrisy and transparent double talk.”

Students Fight Housing Discrimination

In 1944, a diverse group of UW–Madison students started a concerted campaign to end housing discrimination.

The focus of student organizers was the list of university-approved private landlords. Students did not challenge the university’s position that landlords had the legal right to discriminate. However, they argued that landlords did not have the right to be listed by the university. Students collected data on housing discrimination, gained the support of faculty and staff, started educational campaigns to raise awareness, and signed petitions—all to end the practice.

In 1950, student organizers were dealt a devastating blow by the UW Board of Regents. Instead of banning discriminatory landlords, the regents opted to only release a statement. In part, it read: “The Regents are unanimous in their belief that the faculty and officers of the UW, throughout the long years of its history, have made an outstanding record in the safeguarding of human rights.” Yet, housing discrimination remained. So too did the students’ energy to end it.

This fight would last more than 20 years, spanning multiple generations of students. Even after the regents passed a resolution banning discriminatory landlords, these discriminators remained on the university’s approved list. The University Housing Bureau did not act to remove them. It feared that more landlords would remove their listings, creating a housing shortage for white students. Only in the most flagrant cases did the university act. Generations of students of color and Jewish students struggled to find housing in Madison, and throughout that period, student organizers remained steadfast in their conviction that discrimination had no place at UW–Madison.

“No Place to Mix”

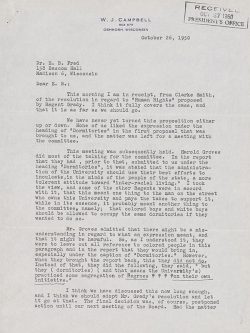

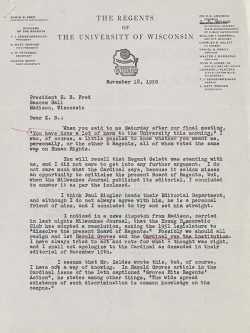

Publicly, the Board of Regents claimed that it rejected policies to end housing discrimination because it did not want to violate the rights of landlords. Private communications revealed another concern. In a set of letters to UW President E. B. Fred, Regent William J. Campbell noted that he was worried about how he would justify interracial living to the people of Wisconsin, “the owners of the university.” He believed they saw interracial living as a step toward interracial marriage and, by extension, interracial children.

Campbell was not alone in his thinking. Discriminatory housing policies did not just impact Black and Jewish students who were denied housing based on their race and religion. White women were also evicted for socializing with Black men. In 1947, Iris Alexander, a white woman, was evicted from her rooming house by her white landlord when she walked home with a Black student following a dance at Memorial Union. The incident received so much attention that the story was covered in a Time magazine article titled “No Place to Mix.” Alumni wrote to Fred, concerned that UW–Madison was not only allowing students of different races to socialize but also encouraging it. Fred responded publicly that he personally deplored “intolerances, frictions, and prejudices which blight our democratic society” and defended the university’s record against discrimination.

“I’m not afraid to stick my neck out and get my name smeared all over. I feel strongly about discrimination, and I am willing to fight it.”

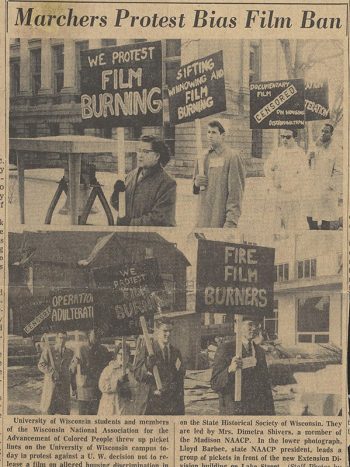

Sifting, Winnowing, and Film Burning

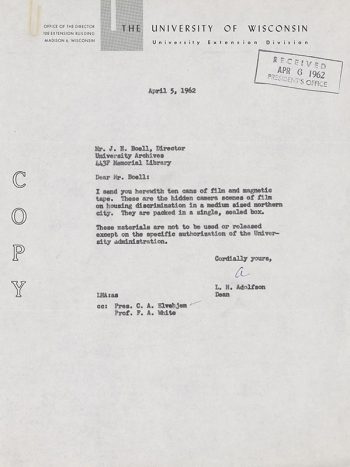

This film was originally produced by the Bureau of Audio-Visual Instruction of the University of Wisconsin Extension Division. The concept for the film was the brainchild of Lloyd Barbee, famed civil rights leader and president of the Wisconsin NAACP, and Stuart Hanisch, a professor in the bureau. Their idea was simple: Barbee, who was Black, and his team would use undercover filming techniques to document housing discrimination in Madison.

With funding in hand and approval from the university, Barbee and Hanisch began filming. Between September and December 1961, they recorded 13 encounters across Madison. The film footage captured the reality of housing discrimination in the city and showed white landlords denying housing to Black residents based solely on their race. University administrators forbade the original film from ever being shown. They feared potential lawsuits from those who were filmed and worried it would create tension between the university and the larger Madison community. University administrators publicly stated the film would be “disposed of.” Barbee, Hanisch, and others believed the film had been burned.

But it was not. It has been sitting in the UW Archives for decades. The film is now unrestricted and available for public viewing after more than five decades.

University Housing

“They had no intention of accepting me.”

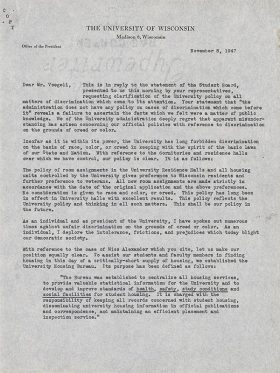

Throughout the student fight to end housing discrimination, university administrators highlighted the University Housing Bureau’s policy of nondiscrimination. Yet, students of color still faced challenges in university residence halls. Segregation plagued room assignments, and Black women were steered toward living in certain dormitories. Harassment and intimidation were commonly reported. While housing officials tried to address these issues, the problems remained.

“This is the first place where I learned tolerance. Here I learned how a group can live together without hate or prejudice and where people accept you without trying to convert you to something you are not.”

Founded in 1944 by the university, the Groves Housing Cooperative was the first interracial housing cooperative at UW–Madison. The house had no racial or religious restrictions; instead, it aimed to create a diverse living environment for college women. The democratic cooperative was controlled and maintained by the women who lived there, which made it affordable and community-oriented. Women like Adela Kalvary, who survived the Holocaust, and Carolyn Konoshima, who survived Japanese American incarceration, found a home and a community at Groves. The house was named after economics professor Harold Groves, who supported its formation. He was an ardent supporter of social justice on campus. While the women who lived at Groves reported positive experiences, few students had the opportunity to live there due to its limited space and resources.

Segregation in Campus Housing

While university-operated dormitories did not expressly discriminate, student organizers pointed out other policies and practices that constituted segregation. The University Housing Bureau was required by state law to give priority access to in-state Wisconsin students, meaning that the primarily white Christian Wisconsin residents were afforded access before Jewish students and students of color, who disproportionately came from out of state.

When marginalized students were able to secure housing in university dormitories, they were often intentionally segregated. The housing bureau had a policy that placed Black women in rooms only with other Black women or found them single rooms before encouraging interracial living. Further, housing bureau staff steered Black women toward certain dormitories like the Groves Housing Cooperative and away from others like Chadbourne Hall, saying that “they would suffer embarrassment by applying.”

Download and read the 1948 letter from Lee Burns (PDF), the Director of Housing, to UW President E. B. Fred about dorm policy.

Dorm Study of Black Students

In spring 1970, the Office of Student Housing commissioned a study on Black students in dormitories following “a series of sporadic incidents … that encompassed elements of racial undertones.” The study found that Black students in dormitories were the target of harassment and physical intimidation. They were more likely to be the focus of complaints from white students especially when two or more Black students gathered to socialize. Black students also voiced concern that decisions regarding floor activities were made by majority vote, which meant that white students effectively controlled decision-making. The report suggested improvements including more training for housefellows, dedicated social spaces for Black students, and “Soul Nights” that would highlight Black culture, music, and food.

LGBTQ Housing

In 1989, hearings held by the Gay and Lesbian Issues Committee noted a pervasive culture of homophobia on campus, especially in university housing. Students reported homophobic slogans and slurs being painted on their dorm room doors, leading many to hide their sexuality. One student-proposed solution was to create separate housing for gay students. At the time, it was rejected by university administrators.

Almost 25 years later, Open House, an inclusive living community for queer students and their allies, was founded in 2013. The goal of Open House is to provide queer students with a safe living space that promotes “awareness, respect, and advocacy for all sexual and gender identities.” While the experience of living in this community is positive, space is limited and students have noted problems for nonbinary people. In response, University Housing opened the Gender Inclusive Community in fall 2021 “to meet the needs of transgender, gender nonconforming, nonbinary, and LGBTQ+ students and allies to select a housing assignment that is inclusive, safe, and comfortable.”

Housing Issues Today

Marginalized students continue to report problems in university housing. In February 2016, a student posted a swastika and multiple pictures of Hitler on the door of a residence hall room in Sellery Hall. In March of that year, a student reported being called racial slurs and spat on in a residence hall. Less than a month later an African American student found a note under her door with racial slurs and obscenities.

“I hear people complaining about policies for inclusion and about the presence of students of color on campus near/in the common areas of my residence hall.”

“Three words: ‘Cinco de Mifflin.’ That particular weekend was the most degrading I have ever felt on university property. Three white males were already drinking and passed out in my dorm; I was doing laundry and they made a comment about how that’s all I was good for—doing laundry.”

“That was the day he stopped talking to me at all.”

“A [woman] had put chopsticks under my pillow because she thought it was funny.”

Sources

- “Negro Co-Ed Says Other Tenants Caused Ouster.” Wisconsin State Journal, Apr. 26, 1940.

- “Jewess, Denied Room, Sues.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), Jan. 10, 1930.

- “University Club Ousts Colored Grad Student.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Oct. 24, 1944, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Pollack, Jonathan Z.S. Wisconsin, The New Home of the Jew 150 Years of Jewish Life at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (PDF), Self-published, 2019.

- Newspaper clippings on housing discrimination during the mid-century in Madison, University General Milwaukee Journal Clippings, Box 1 and 2, “Admission-Discrimination” Folder, 1922–77, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Negro Co-Ed Says Other Tenants Caused Ouster.” Wisconsin State Journal, Apr. 26, 1940.

- “Negro Co-ed Still Lashed, She Complains.” Wisconsin State Journal, May 24, 1940.

- “University Club Ousts Colored Grad Student.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Oct. 24, 1944, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Curti, Merle. “Oral History Interview: Merle Curti.” Interview by Donna Taylor. 1973, OH #027, Oral History Project, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “University Club History.” Office of the Secretary of the Faculty website.

- Seyforth, Scott. “The Life and Times of Carson Gulley.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 99, no. 4 (2016): 2-15.

- For more information on disability and housing at UW–Madison, see McBurney Disability Resource Center Records (1965-2009), Box 4, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Negress Denied Room; U.W. Student Board to Investigate.” 31 March 1949, Box 26, “Racial Discrimination, Disturbances about, on the University campus” folder, Chancellor’s Misc Files; General Subject Files – Discrimination-Enrollment, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Housing muddle can be cleaned by university.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Apr. 1, 1949, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Letter from Board of Regents Secretary Clarke Smith to President E.B. Fred, 17 November 1950 and 5 December 1950, Box 145, Committee on Human Rights Folder, Chancellors General Correspondence 1950–51 Committees, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Memo on Regent Action, August 8, 1952, Box 24, “Discrimination – Ann Emery and Langdon Hall” folder, Chancellors Miscellaneous Files, General Subject Files – Discrimination, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Letter from Regent Campbell to E.B. Fred regarding the Grady Resolution, October 26, 1950, Box 145, Grady Request Folder, Chancellors General Correspondence 1950-1951 Committees, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Landlord Evicts Co-Ed When She Dates Negro.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), October 30, 1947, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Communications and newspaper clippings on the Iris Alexander case, Box 26, “Discrimination – Iris Alexander Case” folder, Chancellor’s Misc Files, General Subject Files – Discrimination-Enrollment, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Education: No Place to Mix.” Time, November 10, 1947.

- Communications and newspaper clippings on the housing film controversy, Box 26, Bias Film (Discrimination) Folder, Chancellor’s Miscellaneous files, General Subject Files – Discrimination – Enrollment, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Rashad, Liberty. “Oral History Interview with Liberty Rashad,” interview by University of Wisconsin–Madison Communications in 2018 in Madison, Wisconsin. Transcript. UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Report of the Student Board Committee Against Discrimination, May 1949, Box 5, “Student Board, Faculty, Regent Documents on Discrimination” Folder, Dean of Student Affairs Kenneth Little subject files, “Discrimination – E”, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Merritt Norvell, Jr. Report on Preliminary Observations on Minority Students and the Residence Hall Community, prepared for the Office of Student Housing, October 1, 1971, University of Wisconsin Housing Archives.

- Roe, Gwyneth. “Polish Born Adela Kalvary Finds Group.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), July 3, 1951, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- University of Wisconsin News Service Press Release on Groves Women’s co-operative house, November 15, 1951, UW–Madison Archies, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Summary of the Recommendations: Report of GLIC,” Dean of Students Records 1968–2010, LGBT Liaison 1962–99, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Schoenmann, Joe. “UW Committee Urges Separate Housing for Gays.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), January 23, 1992. UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Separate but Equal,” Badger Herald (Madison, WI), January 24, 1992. UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Open House Living Community.” University Housing website.

- Fjelstad, Elise. “Beyond the Binary: Gender Inclusive Community expands housing options for trans, gender-nonconforming residents.” Badger Herald, December 2, 2021.

- “Gender Inclusive Affinity Community.” University Housing website.

- Savidge, Nico. “Student disciplined for posting swastikas, photos of Hitler on dorm room door.” Wisconsin State Journal, Last modified February 18, 2016.

- Zhong, Xiani. “UW First Wave scholar subjected to hateful language, spit on face in campus dorm.” Badger Herald, Last modified March 13, 2016.

- Savidge, Nico. “UW-Madison launching another investigation after student finds racist note.” Wisconsin State Journal, Last modified April 1, 2016.

- Walters, Anna. “When home doesn’t feel like home: How racism in world, on campus continues in dorms.” Badger Herald, Last modified September 30, 2020.

- Washington, Reonda and et al. “The Color of Drinking: An exploratory study of the impact of UW–Madison’s alcohol culture on students of color.” (PDF) University Health Services, UW–Madison.

- To learn more about The Color of Drinking Study, visit “Color of Drinking.” University Health Services.

For more details on sources and to request full footnotes, please contact the Public History Project at publichistoryproject@wisc.edu.

In conclusion

“True resistance begins with people confronting pain … and wanting to do something to change it.”

As we fearlessly sift and winnow through the university’s past, many hard truths emerge. We also find hope, and the ever-present possibility of change for the better. The university has changed in many ways across its history, often because members of the campus community have demanded it.

We believe that reckoning with our history can lead us to a better future, and that unless we acknowledge and learn from our past, we cannot move forward together. The future is not yet written. What happens next is up to us.

The UW–Madison Public History Project was made possible with support from the Office of the Chancellor using private funds.