The Early Years

Teejop

The University of Wisconsin–Madison is in Teejop (“four lakes”), part of the ancestral homeland of the Ho-Chunk people.

The land on which UW–Madison now stands has been continuously inhabited for at least 12,000 years, since the last glaciers retreated. Ho-Chunk people lived here in villages, where they planted fields of corn, harvested the wild rice that used to grow along the shores of the lakes, gathered mussels, hunted, and fished. Ho-Chunk people, then and now, understand the land as sacred, and the region’s springs, lakes, and rivers as spiritually connected to them as a people. Despite the repeated efforts of settlers and the U.S. government to expel them during the 19th century, Ho-Chunk people persisted, endured, and continue to live here in Teejop.

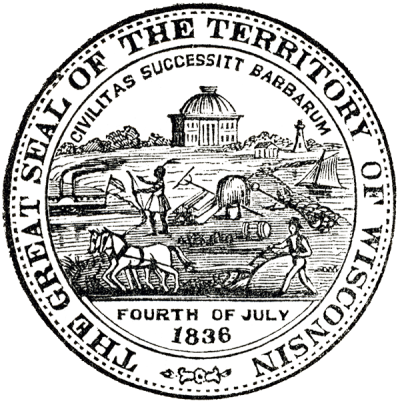

1836 Territorial Seal

The founders of the Wisconsin Territory represented their project as the triumph of their “civilization” over what they considered Native American “barbarism.” The official 1836 territorial seal featured the figure of a white man breaking the land with a team and plow. He was surrounded by ships, lighthouses, and steamboats, the elements of a modern commercial economy. The large, domed capitol building represented the institutions of a new government, which 12 years later established the University of Wisconsin.

A University Built on Ho-Chunk Land

To establish a university, you need land. A place to build. For UW–Madison, as for the entirety of the United States, the land was taken from Indigenous peoples.

The land on which the city of Madison and the university stand are part of the ancestral homeland of the Ho-Chunk people. In an 1825 treaty, the United States recognized it as such. But in an 1832 treaty, the U.S. demanded that the Ho-Chunk surrender a huge area of land, including this region. The Treaty of 1832 may be our campus’s most important document: it is the legal basis on which the city and the university could be built and on which non-Ho-Chunk people can now reside.

The Treaty of 1832 took place under duress—what one U.S. official called “the blended grounds of conquest & contract.” A U.S. army occupied large parts of Wisconsin, and the Ho-Chunk had no choice but to sell the land. The treaty demanded that they leave the region, and U.S. authorities repeated this demand in an 1833 meeting with Ho-Chunk leaders just a few miles from here, in today’s city of Middleton. Decades of ethnic cleansing followed, during which the state and federal governments repeatedly sent soldiers to banish the Ho-Chunk from Teejop and the rest of their homeland. But the Ho-Chunk people’s spiritual connection to this land and its waters and to their ancestors could not be broken by treaties and violence. Many Ho-Chunk people refused to leave Wisconsin, and many others quickly returned.

The land the U.S. took from the Ho-Chunk in 1832 was the most important way in which the university benefited from the seizure of Indigenous people’s lands. The university also received the profits from grants of “public lands” that the federal government had seized from Native people in other treaties. For example, under the Morrill Act, signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862, the University of Wisconsin received 235,530 acres in northern Wisconsin, which it sold for a $303,439 profit. Adjusted for inflation, this represents nearly $5 million that still benefits the university today.

The University of Wisconsin was founded in 1848, in the same year as the State of Wisconsin. Native people remained in Teejop and throughout Wisconsin, but for the first century of the university’s life not one Native person from Wisconsin graduated from the university. Although the university stands on ancestral Ho-Chunk land, it was not until the 1970s that Ho-Chunk students were able to make a place for themselves here.

Playing Indian

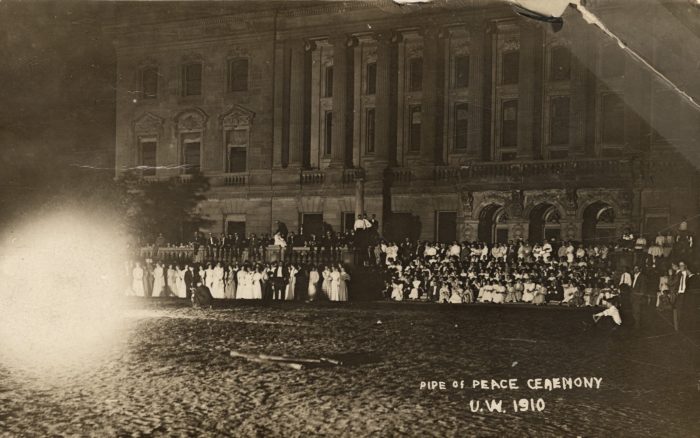

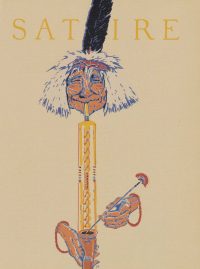

Between the 1890s and the 1930s, the Pipe of Peace ceremony drew large crowds of students to Library Mall during commencement week. In this parody of Native American life, white students dressed in “Indian” costumes and passed an elaborate pipe decorated with the ribbons of each graduating class.

During this era, no Native Americans graduated from the university and only a few briefly attended. On reservations during these same years, Native Americans were prosecuted by federal authorities for carrying out their own sacred traditions, and children were stolen from their parents and forcibly reeducated in an effort to strip them of their cultures and languages. Meanwhile, white students here “played Indian,” appropriating misconceived ideas about Native Americans. The Pipe of Peace was such a foundational part of campus culture that it can still be seen today in decorative features on the doors of the Memorial Union. Read Pipe of Peace presentation materials from 1913, 1921, and 1923 (PDFs).

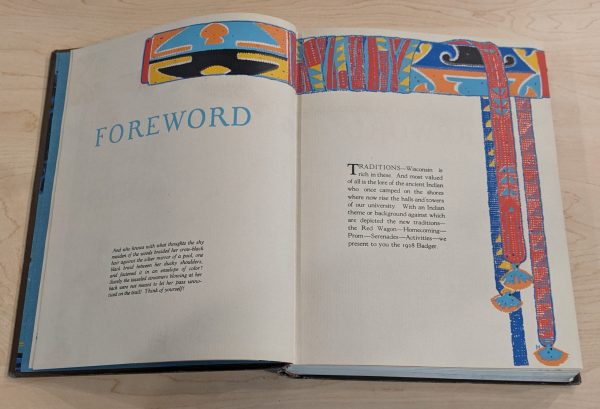

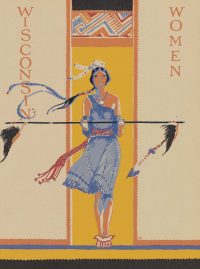

In 1928, the UW–Madison Badger yearbook theme was “Traditions,” which used what editors called “proud Indian themes.” It wrongly equated university events such as homecoming, prom, and other social activities with Native American cultural practices. The yearbook displayed caricatures of Indigenous peoples alongside a spread that glorified the Pipe of Peace ceremony.

The Firsts

1950 Geraldine Harvey

These individuals are the first known students of their respective ethnic or cultural identities to graduate from UW–Madison. Although they may have appreciated the opportunity to study here, being the first was not easy. Many expressed feelings of isolation and found it challenging to connect with other students. Some were barred from attending campus events and joining certain social organizations. Many were forced to endure discrimination and harassment in the classroom. Yet these scholars represent important milestones in the story of resistance and perseverance on campus.

1865 Phillip Stein

Phillip Stein was the first known Jewish student at UW–Madison. Despite being the youngest in his class, he graduated with valedictorian honors in 1865. He returned to earn his law degree in 1868. As an active alumnus, he helped pave the way for many other Jewish students and even hired some of them to work for his Chicago-based law firm.1869 First Women to Graduate

In 1869, Clara Bewick, Anna Headen, Jane Nagle, Helen Noble, Elizabeth Spencer, and Ella Ursula Turner were the first six women to graduate from UW–Madison. President Paul Chadbourne did not believe women should receive the same degree as men. He stated, “Never will I be guilty of the absurdity of calling young women bachelors.” The Board of Regents ultimately disagreed with Chadbourne and awarded them bachelor’s degrees in 1869.

1875 William Noland

William S. Noland was the first known African American to graduate from UW–Madison. He received his degree in 1875 and in the class album described himself as follows: “He has a sanguine temperament, a logical mind, and is a good writer & speaks in public with a slight hesitancy ... and has ‘paddled his own canoe’ most of the time since his boat was launched on the sea of life.” Although he attended the law school briefly, little is known of his later life until his death by suicide in 1890.

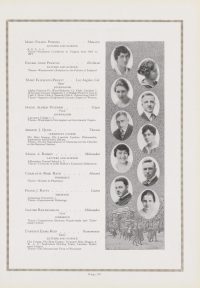

1906 William F. Terrazas

William “Cesar” F. Terrazas was the first known Mexican student at UW–Madison. Graduating in 1906 from the agriculture department, he was an active member of the International Club. The statement he chose to include in his graduating yearbook hints at the solitude he may have felt during his time at the UW: “I traveled among unknown men / In lands beyond the sea; / Nor, Mexico, did I know till then / The love I bore to thee.”

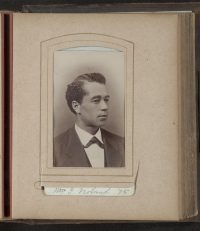

1910 Guok-Tsai Chao

Guok-Tsai Chao graduated in 1910 as a part of the first cohort of Chinese students at UW–Madison. In the Wisconsin Alumni Magazine he expressed the value of intercultural exchange: “It is undoubtedly the duty of the Chinese students to learn; but it is also their duty to be learned and studied. The ignorance of China on the part of the Americans has been the cause of numerous deplorable misunderstandings and the result of lack of intercourse between the two peoples. To remedy this situation, nothing can be better than for Chinese students to mingle with the Americans and let them learn from the living representatives instead of from the colored tales of China.”

1918 Mabel Watson Raimey

Graduating in 1918, Mabel Watson Raimey was the first known African American woman to receive a degree from UW–Madison. Raimey went on to attend Marquette Law School, working during the day as a legal secretary to put herself through school. The American Bar Association refused to admit Black lawyers, so Raimey passed as white. “Nobody asked” about her race, Raimey said. “I never told.” She eventually became the first African American woman to practice law in Wisconsin.

1920s Arthur J. Petrie

Attending UW–Madison in the 1920s, Arthur J. Petrie was a blind law student who persevered despite a lack of disability accommodations by the university. Petrie was the first known student with a disability to attend the UW, and an article from the Madison Capital Times alludes to the loneliness and isolation he experienced: “He travels alone, he goes to and from classes alone, and has trained himself to be as independent as possible.”1950 Geraldine Harvey

Geraldine Harvey earned a master’s degree in education from UW–Madison in 1950, becoming the first known Native American graduate of the university. Born in Wisconsin to a Chippewa father and an Oneida mother, Harvey spent the majority of her life in Taos, New Mexico. She taught Menominee, Sioux, Apache, Sac and Fox, Cheyenne, and Pueblo children.

1956 Robert Powless

Earning a bachelor’s degree in secondary education in 1956, Robert Powless was the first known Native American man to graduate from UW–Madison. A proud member of the Oneida Nation, Powless was a dedicated housing advocate, a passionate educator, and a Korean War veteran. A tireless champion for the academic value of Indigenous studies, he founded in 1972 the American Indian Studies program at the University of Minnesota–Duluth.1957 Ada Deer

Advocate and civil servant Ada Deer earned her social work degree from UW–Madison in 1957. A member of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, Deer has been a boundary breaker throughout her career: she was the first female American Indian undergraduate to earn a degree at UW–Madison; the first American Indian to receive a master’s degree in social work from Columbia University; the first woman to chair the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin; the first American Indian woman in Wisconsin to run for U.S. Congress; and the first American Indian woman to be appointed assistant secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the U.S. Department of the Interior under the Bill Clinton administration.

1982 Song Kue

Song Kue is the first Hmong to graduate from UW–Madison, earning a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1982. Kue is an exception of his generation since most Hmong refugees who came to the U.S. as adults did not get the opportunity to pursue higher education. While in Laos, he studied French and began to teach himself English using a French–English dictionary. In the U.S., he enrolled in an English as a Second Language (ESL) program for two years before being accepted at UW–Madison. Following graduation, the U.S. government recruited Kue to design data chips for the black boxes used in fighter jets.

Women at the University

For nearly 100 years, women at UW–Madison were largely segregated from their male peers.

Fearing that the Civil War could cause a precipitous drop in student enrollment and threaten faculty employment, UW–Madison admitted its first female students to a separate and segregated college in 1863. The earliest female students were white Christian women of a high social class. The first cohort of women was met with ire by some male students on campus who viewed their presence as a humiliation. The Board of Regents and faculty pushed for coeducation and not a separate college for women. But President Paul Chadbourne, a staunch opponent to coeducation, resisted this effort. By 1874, after Chadbourne left UW–Madison, the regents approved full coeducation due to funding concerns and the hassle of duplicating courses for men and women.

Outside of the classroom, dormitories such as Lathrop Hall and Chadbourne Hall (originally called Ladies Hall) were reserved for women and placed away from men’s housing. Women had separate gym facilities and were forbidden from participating in certain student activities like band. Men and women were not allowed to socialize with each other in campus spaces such as the University Club and Memorial Union. In all spaces, the university monitored and policed women’s behavior. Female students were required to adhere to stricter curfews and social regulations, were monitored closely by live-in housemothers and female university administrators, and often faced stricter punishment than their male classmates did.

Sources

- “Treaty Day,” Our Shared Future website.

- Lee, Robert and Tristan Ahtone. “Land Grab Universities.” High Country News, March 30, 2020.

- Deloria, Philip Joseph. Playing Indian. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Pollack, Jonathan Z.S. Wisconsin, the New Home of the Jew 150 Years of Jewish Life at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. (PDF) Self-published, 2019.

- Transforming Women’s Education: The History of Women’s Studies in the University of Wisconsin System. Madison, Wisconsin: Office of University Publications for the University of Wisconsin System, Women’s Studies Consortium, 1999.

- Knutson, Käri. “UW Women at 150: Celebrating 150 years since first women got undergraduates degrees.” UW–Madison News (blog), September 27, 2018.

- Knutson, Käri. “More than a footnote: Remembering the life of William S. Noland, the first known Black graduate of UW–Madison.” UW–Madison News (blog), March 3, 2021.

- University of Wisconsin–Madison, Badger Yearbook Vols. XX (1906), XXVIII (1914), 72 (1957), 73 (1958), 84 (1969).

- “History.” Wisconsin China Initiative, 2021.

- Chao, Guok-Tsai. “Why I Came to Wisconsin.” Wisconsin Alumni Magazine, November 1909.

- Knutson, Käri. “When perseverance is the only option: Mabel Watson Raimey.” UW–Madison News (blog), March 3, 2021.

- “Blind U.W. Student Takes Notes, Typewrites, Finds Way Without Assistance.” Madison Capital Times (Madison, WI), May 31, 1924.

- “Geraldine Harvey.” Rivera Family Funeral Home, Accessed December 10, 2021.

- Lundy, John. “Robert Powless, Native American educator and housing advocate, dead at 87.” Duluth News Tribune, April 28, 2020.

- Vainio, Ivy. “Remembering Dr. Robert Powless.” Duluth Reader, April 30, 2020.

- Knutson, Käri. “Ada Deer: A lifetime of firsts.” UW–Madison News (blog), December 18, 2018.

- Cassidy, Otehlia. “Hmong Life in Madison: Fostering a vibrant community despite barriers.” Madison Magazine. Last modified June 13, 2022.

- Cronon, Edmund David, and John W. Jenkins. The University of Wisconsin: A History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

For more details on sources and to request full footnotes, please contact the Public History Project at publichistoryproject@wisc.edu.

In conclusion

“True resistance begins with people confronting pain … and wanting to do something to change it.”

As we fearlessly sift and winnow through the university’s past, many hard truths emerge. We also find hope, and the ever-present possibility of change for the better. The university has changed in many ways across its history, often because members of the campus community have demanded it.

We believe that reckoning with our history can lead us to a better future, and that unless we acknowledge and learn from our past, we cannot move forward together. The future is not yet written. What happens next is up to us.

The UW–Madison Public History Project was made possible with support from the Office of the Chancellor using private funds.