Student Life

A Culture of Bigotry

Life at UW–Madison was challenging for early marginalized students. Unlike the bustling social calendar of our current campus, opportunities to connect with peers were limited in the university’s first decades. Nonwhite students were intentionally excluded from the most well-attended events on campus, like prom. Other popular campus clubs organized and promoted activities that centered racist entertainment like minstrelsy. University leaders condoned this behavior.

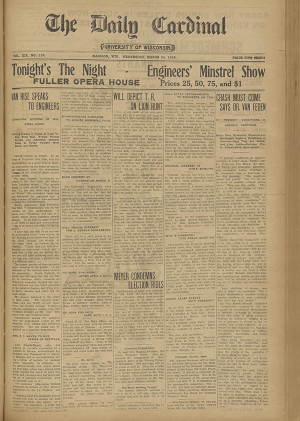

Minstrelsy

By the end of the 19th century, blackface minstrelsy was the most popular form of entertainment in the United States. Minstrelsy relied on racist depictions that dehumanized Black people by portraying them as incompetent and idiotic. In turn, these racist stereotypes were spread and then used as justification to deny Black people full and equal participation in society—from education and voting to housing and employment.

With the wide availability of sheet music and how-to guides, college fraternities and student organizations across the United States began to host minstrel shows as a form of fundraising. At UW–Madison, this practice continued for more than a century. Many clubs hosted minstrel performances, but the most well-attended and financially successful shows were the “Wisconsin Senior Engineers World Famous Minstrel Productions” from 1903 to 1920. White male students were the main performers, and white female students supported the shows by creating costumes and promoting and attending the events. White faculty and staff also attended. President Charles Van Hise praised the production, saying, “I congratulate you on the success of this undertaking. It shows your versatility … to be able to adapt [oneself] to all sorts of men and surroundings.” Although blackface lost popularity after the Civil Rights Movement, it continued to appear on campus in the form of racist fraternity parties into the 1980s.

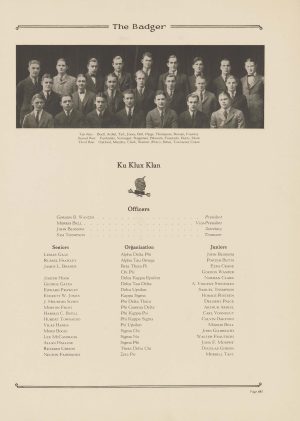

The Klan

Between 1919 and 1926 two student organizations at UW–Madison took the name “Ku Klux Klan” without objection from university administrators or student government. The first was founded in 1919 as an interfraternity honor society composed of student leaders. There is no evidence this group was affiliated with the national organization, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Yet, the members’ choice of that name signals an identification—and at the very least, no meaningful discomfort—with the widely known racially violent actions of the Reconstruction-era Klan, which had recently been celebrated in the blockbuster 1915 film The Birth of a Nation. The student senate, which in that era often asked student organizations to change their names for a variety of reasons, did not object to the Klan name.

In 1924 a Klan-affiliated fraternity, Kappa Beta Lambda (KBL, for “Klansmen Be Loyal”) was established at UW–Madison. A Milwaukee Klan newspaper praised this group’s commitment to the Klan principles of “White Supremacy, Restricted Foreign Immigration, Law and Order.” The emergence of the second group inspired the first group to change its name to the cryptic and ambiguous “Tumas.” That organization persisted for a few more years. Kappa Beta Lambda fell into academic probation due to poor grades and received only four pledges in 1926. It ceased to exist later that year.

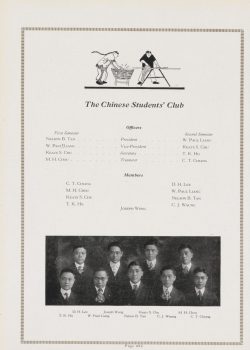

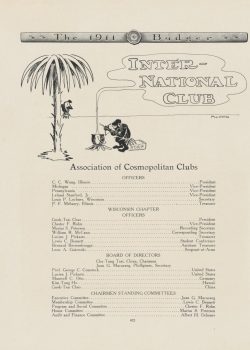

Racism in the Yearbooks

Marginalized student organizations on campus were often disrespected by their white peers and treated as the punchline of jokes. This can be seen clearly in yearbooks throughout the time period, where stereotyped caricatures were used to depict nonwhite student organizations. Editorial decisions were made by the Badger yearbook staff, not individual student groups.

Claiming Space

“Claiming your space here is a piece to making it better for the people who come after you.”

In the early decades of the 20th century, student organizations routinely excluded nonwhite and non-Christian students, and racist activities were commonplace. The Badger yearbook publication printed countless jokes with racist punchlines and represented nonmajority students and student organizations with disrespectful and demeaning caricatures.

Yet even when their activities were mocked or derided, marginalized students claimed space on campus and created their own groups where differences were accepted and celebrated. These spaces were important sites for students to build community and to fight alienation on campus. The following is a list of some of the earliest groups created to serve diverse student populations. Today, more than 900 student organizations exist at UW–Madison, and many of them are dedicated to supporting marginalized students on campus.

1903 International Club

The International Club was founded by Japanese student Karl Kawakami with the motto “Above All Nations Humanity.” In addition to planning social activities, the club greeted new international students, helped them find housing, and introduced them to the university.

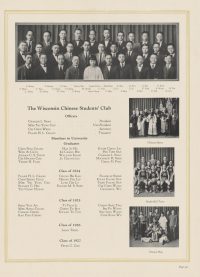

1909 Chinese Students’ Club

The Chinese Students’ Club was organized with the goal of “promoting a better relationship between American and Chinese people.” It presented Chinese theater, sports, and history to campus. Today multiple organizations exist for Chinese students.

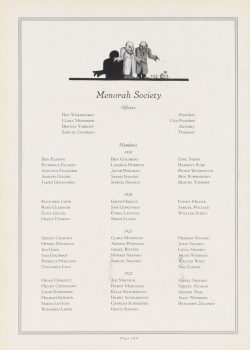

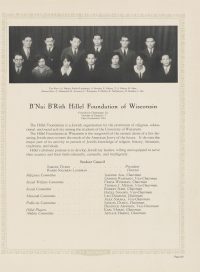

1911 Menorah Society, Hillel

The Menorah Society was founded as a literary and debate club, becoming the first explicitly Jewish organization at UW–Madison. When UW–Madison Hillel was founded in 1924 to support Jewish students on campus during a time of rising antisemitic sentiment, it absorbed the Menorah Society group. Hillel continues today.

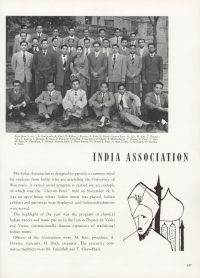

1951 India Association

The India Association was founded to create bonds between American and Indian students. The organization continues today as the Indian Students Association.

1953 Africa Union

A group of students from Africa formed the Africa Union to correctly interpret African culture and customs for the university at large. The organization continues today as the African Students Association.

1966 Wisconsin Black Student Union

The Wisconsin Black Student Union (WBSU) rose to prominence during the 1969 Black Student Strike. The group was originally founded in 1966 as the Concerned Negro Students and soon changed its name to the Black People’s Alliance. The students stated their guiding motivation as “the Negro has to determine his goals instead of having it done for him.” The group continues today to advocate for the needs of Black students.

1967 Handicapped Students Association

A group of wheelchair-using students and their faculty adviser, real estate professor James Graaskamp, founded the Handicapped Students Association (HSA). It was later renamed Pathways to Independence. In the association’s mission statement, the students defined themselves as “a group of individuals who are interested in finding solutions to problems encountered by the physically disabled students on campus.” Today, multiple organizations exist for students with disabilities.1968 Wunk Sheek

Native students formed the Coalition of Native Tribes for Red Power (CNTRP), later renamed Wunk Sheek, to serve “students of Indigenous identity and members of the UW–Madison community interested in Indigenous issues, culture, and history.” Wunk Sheek is currently housed within the American Indian Student and Cultural Center (AISCC) with six other student organizations. The development of green space for Levy Hall will displace this important center. During this cycle of relocation, students have repeatedly expressed concerns that many places across campus inadequately serve the needs of Native students.

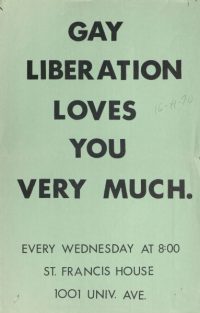

1969 Madison Alliance for Homosexual Equality

The Madison Alliance for Homosexual Equality (MAHE) became the first gay liberation group in the state of Wisconsin and on UW–Madison’s campus when it held its first meeting in November 1969. The initial announcement stated that the group was “dedicated to the creation of a society characterized by responsible sexual freedom.” It continued, “We do not seek tolerance; we demand human dignity and respect.” Today, there are multiple organizations supporting LGBTQ+ students.

1988 Hmong American Student Association

The Hmong American Student Association (HASA) was founded in 1988 following the hiring of a Hmong bilingual and bicultural adviser for Southeast Asian students at UW–Madison. In response to student appeals, Hmong staff agreed to sponsor the formation of a Hmong American student organization. HASA serves to this day as a vital resource for students, promoting higher education and providing opportunities for leadership.

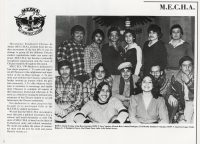

1970 MEChA

Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Aztlán (MEChA) was founded to promote Chicano/a history, culture, and arts with an emphasis on the value of higher education and community engagement. The MEChA house is located at 206 Bernard Court. In addition to the AISCC, the development of the block for Levy Hall will also displace this important center.

Discrimination in Greek Life

In the 1940s, student enrollment in Greek-letter organizations boomed as World War II veterans returned home. Historically, fraternities and sororities on college campuses were founded to serve as social organizations for white Christian students. As central elements of campus social life, these student organizations played important roles in the culture of exclusion and racism that created a hostile environment for marginalized students. Parties with racist themes were commonplace. When Black and Jewish fraternities and sororities sought to participate in campuswide Greek-letter activities, they were subjected to harassment including slurs and minstrel caricatures from white Greek-letter organizations.

The discrimination in fraternities and sororities was coupled with exclusionary membership clauses demanded by national organizations that prevented integration. A report from 1949 noted that 20 out of the 52 Greek-letter organizations on campus had a discriminatory clause in their constitutions that barred nonwhite membership. Even as education campaigns pushed for an end to bigotry and exclusion, 14 organizations still had such clauses in their charters as late as 1954.

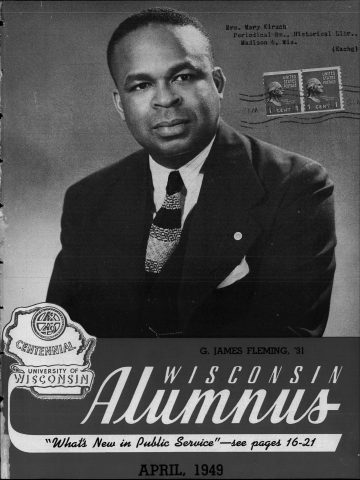

G. James Fleming

G. James Fleming, a Black student from New York, was forbidden from pledging the honors speech fraternity Delta Sigma Rho in 1932. Its national charter stated: “no negro, regardless of his achievements, may become a member of the fraternity.” The Daily Cardinal demanded the university support Fleming’s admission, and the UW chapter petitioned the national organization to vote to remove the clause. The vote did not pass. In the April 1949 Wisconsin Alumnus magazine Fleming was celebrated for his role as the secretary of the American Friends Service Committee, which was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 1947. He was mistakenly listed as being a member of the fraternity.

Jewish Greek Life

Established in 1921, the Phi Sigma Delta fraternity and Alpha Epsilon Phi sorority became the first Jewish Greek-letter organizations at UW–Madison. Early Jewish fraternities faced challenges when trying to establish chapters. Despite the barring of non-Christian and nonwhite students from other organizations, university administrators claimed that racially or ethnically specific fraternities went against the inclusive mission of the university. Dean Scott Goodnight stated misleadingly that “there have heretofore been no national organizations on our campus which confined their membership to any given race or creed.”

The Apex Club

Even with their own organizations, Jewish fraternities and sororities struggled to participate in the larger culture of Greek life. Established in 1928, the Apex Club organized mixers and dances for Greek-letter organizations with the explicit purpose of excluding Jewish Greek-letter organizations. By holding its events off campus, Apex Club thought it could evade the university’s antidiscrimination rules. In January 1929, an article about the club’s discriminatory practices ran in the Capital Times newspaper. In response to the bad press, the university shut the club down.

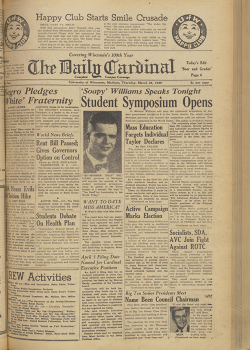

Sonny Sykes

Weathers “Sonny” Sykes became the first Black man to join an otherwise all-white fraternity at UW–Madison, the Jewish fraternity Phi Sigma Delta, in 1949. Jewish fraternities did not limit membership by race or religion. But Sykes’s pledging became so controversial that Phi Sigma Delta released a letter to the public explaining its decision to accept him. The fraternity noted Sykes was unanimously welcomed by the fraternity and that he “is just another Phi Sig pledge; we can look at him no other way.”

“Heartache on Campus” by Mrs. Glenn Frank

Though the fight for desegregation in fraternities and sororities would not begin in earnest until 1949, debate over the exclusionary practices of these organizations had already reached public forums by the 1940s. Published in Woman’s Home Companion magazine in 1945, the widow of former UW–Madison President Glenn Frank wrote an article titled “Heartache on Campus.” Mary Frank did not critique the exclusionary practices of local Greek chapters, but she did highlight the “heartache” felt by those denied a bid to a Greek organization. She focused on excluded students’ experiences who, she thought, felt a “deep sense of inferiority” when they were not selected for membership. George Starr Lasher, the editor-in-chief of the Rattle of Theta Chi, admitted the existence of “unwritten rules” that barred minorities’ access to sororities and fraternities, but he decried Frank for not presenting any statistical data on minorities being denied access and relying on anecdotes instead.

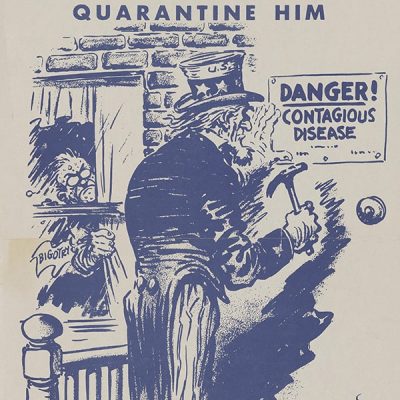

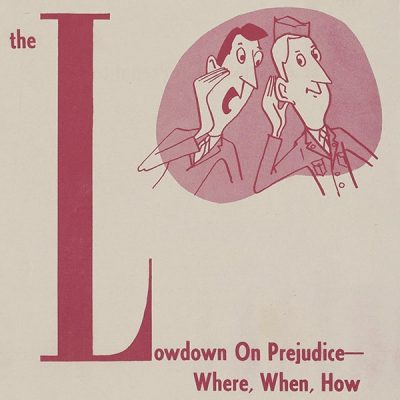

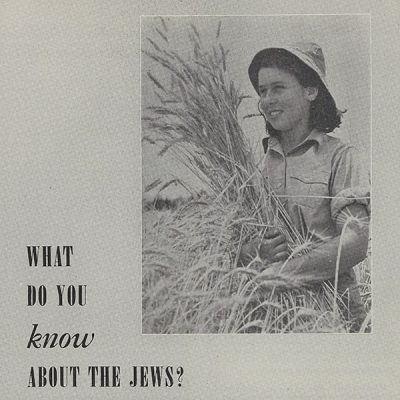

Educational Pamphlets

Facing accusations of discrimination in Greek-letter organizations, the Interfraternity Association created the Inter-Racial Committee in 1947. The committee surveyed members of Greek-letter organizations on integration; it identified members’ racism, not discriminatory clauses, as the root of the problem. Its conclusion was that fraternities and sororities should focus on antibigotry education. These educational pamphlets were distributed to fraternities and sororities across campus to try to reduce racism in the Greek-letter community.

The 1960 Clause

As opinion on campus shifted toward supporting integration during the 1950s, students and faculty began organizing for an end to discriminatory clauses in Greek-letter organizations. After mounting media attention, the UW Board of Regents and faculty acted. In 1952, they formally approved the “1960 Clause,” which mandated that all university-approved housing units (including fraternities and sororities) remove discriminatory language in their foundational documents by July 1960.

It took more than 14 years from initial organizing efforts until the last discriminatory clause was removed from UW–Madison’s campus. But integration in practice was slow to take root. While formal discriminatory clauses were no longer written into organizational documents, Greek-letter organizations were still free to accept or deny individual members. Fraternities and sororities remained highly segregated spaces.

The Delta Gamma Case

In 1962, leaders at UW–Madison moved to expel the Delta Gamma sorority from campus following the news that the group’s sister chapter at Beloit College unpledged a woman because she was African American. But in an act of protest, members of all of the Greek organizations on the UW’s campus walked two-by-two from Langdon Street to Dean of Students Leroy E. Luberg’s office. They demanded that Delta Gamma remain on campus. Those demands were met when the Faculty Senate voted to allow Delta Gamma to continue operations.

The Divine Nine

“I think Black Greek life is so important especially at PWIs (predominantly white institutions) because … you’re in so many spaces where you just feel alone and you feel like … you can’t connect with people. You’re not being heard. But [in] these organizations not only do you have that support but they also uplift you. … [W]hen I spoke out [about the 2019 homecoming video] I felt comfortable because I knew I had my sisters, I had the grad chapter, and being in this chapter has instilled a lot of values in me to be confident in myself and my abilities.”

Black Greek-letter organizations (BGLOs) have a long and storied history. These organizations were founded at the turn of the 20th century as cultural, educational, social, and philanthropic hubs for Black students. Each organization has its own unique customs, but the shared mission is to cultivate lasting social bonds, provide educational support, and produce critically engaged members who contribute to their communities.

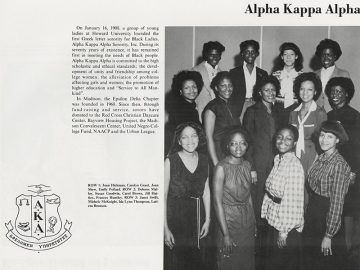

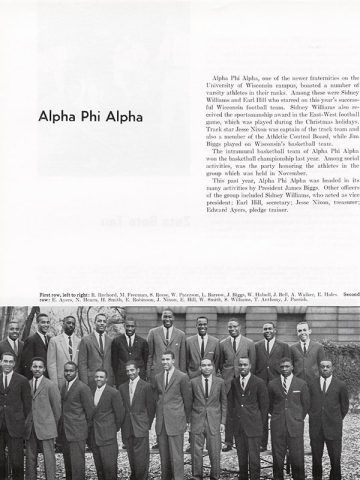

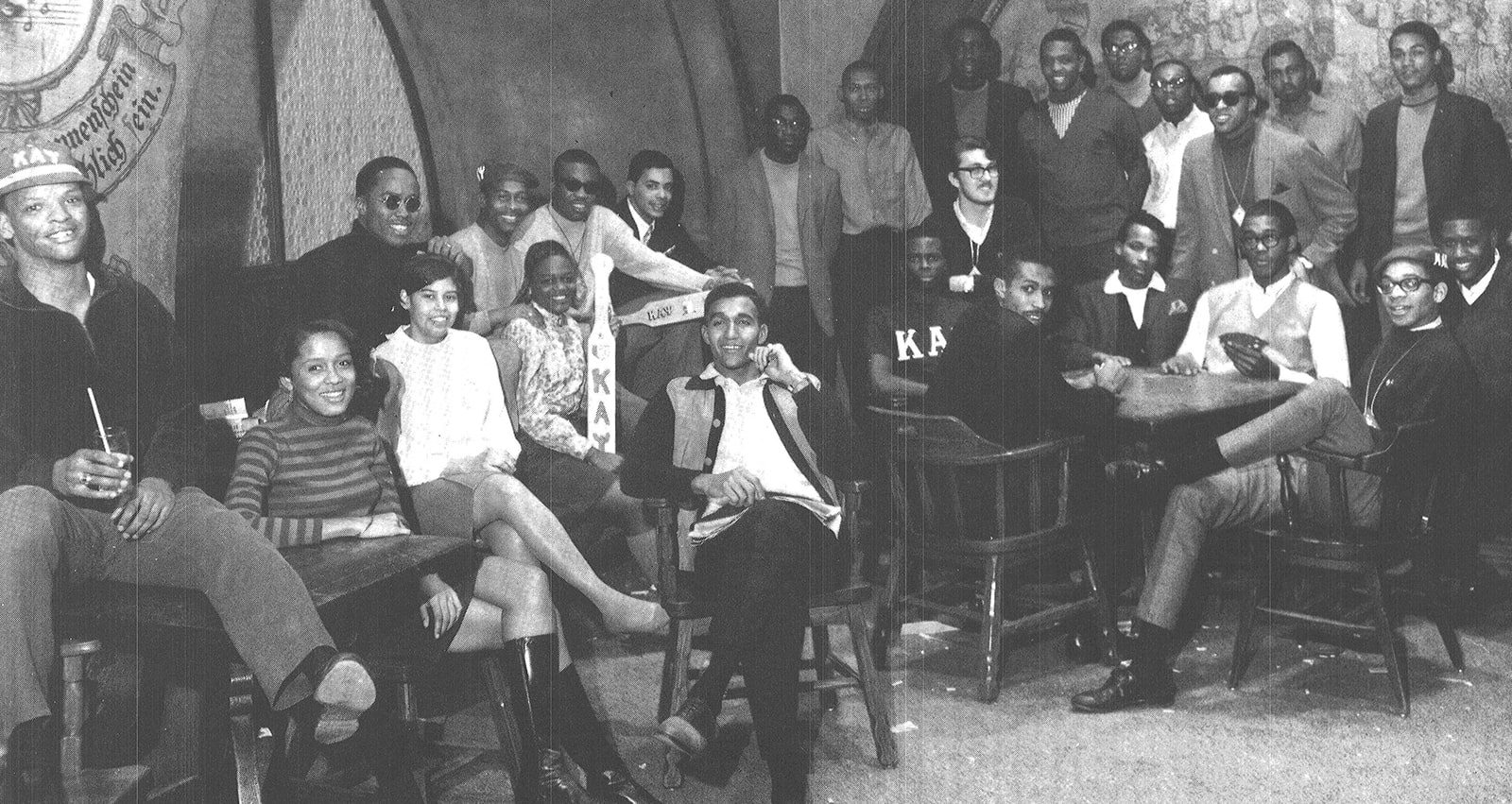

At UW–Madison, BGLOs have played an important role in the campus community. They have hosted social events, raised money for philanthropic causes, and advocated for civil rights. The first BGLOs established at UW–Madison were Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc., in 1946 and Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., in 1947.

In the 1960s, coinciding with the Civil Rights Movement, many BGLO chapters were newly chartered, and their memberships flourished. As BGLOs grew, they created their own managing body, the Black Greek Council. The Black Greek Council collaborated with the Interfraternity Council to advocate for Black Greek life within traditionally white Greek-letter organizing structures. The UW–Madison chapter of the first Black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., was chartered in 1968.

Today, BGLOs continue to have an active role in the campus community, despite not having dedicated houses and being chronically underfunded. UW–Madison has been home to eight of the nine nationally historic BGLOs, known as the Divine Nine. All nine organizations are governed by the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) at a local and international level.

Breaking Racial Lines: The Formation of Black Greek Letter Organizations at UW–Madison

Fraternity & Sorority Life Today

Discrimination has continued in Greek life despite integration. In the 1980s, numerous racially themed parties at Greek houses on Langdon Street garnered national headlines. As recently as 2016, fraternities have come under scrutiny for creating a hostile and discriminatory environment. It was reported then that one organization’s white members used “racist and bigoted slurs” after a Black member told them to stop. While the campus Committee on Student Organizations suspended the organization, it was eventually reinstated.

Students of color continue to form their own cultural-based fraternal organizations (CBFOs). In 2003, the Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) was formed as the governing body for multicultural and multiethnic fraternities and sororities by two organizations, Alpha Pi Omega Sorority, Inc., and Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. The MGC mission is to “foster a unified multicultural community, to promote scholarship, service, respect, camaraderie, and cultural awareness.”

A 2019 external review of UW–Madison’s fraternities and sororities examined the problems that Greek-letter organizations continue to face. Despite being part of Greek life, students from multicultural and historically Black Greek-letter organizations (BGLOs) found Langdon Street—where most fraternities and sororities are housed—to be “not a welcoming place for them.” The survey highlighted the continued discomfort students of color experience among organizations that remain predominantly white. The external review recommended the entire university “place singular focus and attention on UW’s history, structures, policy, and practices and how they lead to or inhibit the recruitment, retention, and belonging of students, faculty, and staff of color.” The university has since established an Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life with full-time staff for the Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) and the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC); raised funds for and opened the Divine Nine Plaza that recognizes the contributions of BGLOs on campus; and dedicated two spaces to MGC and BGLOs in Memorial Union.

Sources

- Cronon, Edmund David, and John W. Jenkins. The University of Wisconsin: A History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

- Barnes, Rhae Lynn. Interview with Nathan Connolly. Backstory Radio. February 8, 2019. Podcast.

- Lott, Eric. Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Roediger, David R. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. New York: Verso, 2007.

- “Van Hise Speaks to Engineers: Commends Success of Minstrel Show.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Mar. 24, 1909, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Messer-Kruse, Timothy. “The Campus Klan of the University of Wisconsin: Tacit and Active Support for the Ku Klux Klan in a Culture of Intolerance.” Wisconsin Magazine of History, Autumn 1993.

- Kantrowitz, Stephen, Floyd Rose, and et al. “Report to the Chancellor on the Ku Klux Klan at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. ” (PDF). April 4, 2018.

- Weaver, Norman Frederic. “The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 1954.

- International Club brochure, Series 20/3/2/5/10 49A5, Student Life Organizations, Records and Related Materials, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “International Club 61 Years Old.” Daily Cardinal, (Madison, WI), Fall Registration Issue 1963, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Chinese Night 1920 program, UW Memorabilia Collection, 1920, Box 10, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “When did Ebony Ball start?” Ask Flamingle (blog), Wisconsin Foundation and Alumni Association. Accessed December 6, 2021.

- “Concerned Negro Students” Group Organized at U.W.” Madison Capital Times, Nov. 28, 1966, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Pathways to Independence,” 12 December 1978, Series 2005/146 40A9, McBurney Disability Resource Center Records (1965-2009), Chancellor’s Committee for Disabled Persons 1978-79, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Organization Instituted for Benefit of Homosexuals.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Jan. 7, 1970, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “History.” OOCities – MEChA, Accessed November 23, 2021.

- Peterson, Angela. “Rewriting Chapters: Resistance to Addressing Discriminatory Practices in University of Wisconsin–Madison Fraternities and Sororities, 1947-1962.” Archive, May 2020.

- Murphy, Peter H. “Fraternities Come Back.” Wisconsin Alumnus Magazine, February 1947.

- Hiller, Burt. “Report to the Committee of Student Life and Interests Concerning Discrimination Clauses in Fraternity Constitutions,” Box 1, Dean of Student Affairs-Inter-Fraternity Affairs Records, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Bar to Negro Stirs Campus.” The Journal’s Madison Bureau, May 15, 1931, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “On the Cover.” Wisconsin Alumnus Magazine, Apr. 1949, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Levine, Mort. “Negro Pledges ‘White’ Fraternity.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Mar. 24, 1949, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Fraternity explains Negro pledging.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Nov. 15, 1949, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Glenn Frank’s wife, Mary Frank, published exclusively under the name “Mrs. Glenn Frank.” Frank, Mrs. Glenn. “Heartache on Campus.” Women’s Home Companion, April 1945.

- Inter-Racial Committee Constitution and By-laws, Box 1, Dean of Student Affairs-Inter-Fraternity Affairs Records, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Report of the Committee on Human Rights.” Box 3, Faculty Document 1041, Human Rights Committee Records, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Discriminatory Clauses Out! Regents Rule Against Clauses After 1960.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Aug. 12, 1952, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Levitan, Stuart D. Madison in The Sixties. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2018.

- “Faculty Lets Delta Gamma Stay.” Wisconsin State Journal, Dec. 4, 1962.

- “UW–Madison Commission to Study Future of Fraternities and Sororities.” Minority Groups, Fraternity Incidents, 11 November 1988, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Wisconsin fraternity suspended over racist, bigoted slurs.” Chicago Tribune, May 18, 2016.

- For more information on the councils within Fraternity and Sorority Life at UW–Madison: “Councils.” Fraternity & Sorority Life.

For more details on sources and to request full footnotes, please contact the Public History Project at publichistoryproject@wisc.edu.

In conclusion

“True resistance begins with people confronting pain … and wanting to do something to change it.”

As we fearlessly sift and winnow through the university’s past, many hard truths emerge. We also find hope, and the ever-present possibility of change for the better. The university has changed in many ways across its history, often because members of the campus community have demanded it.

We believe that reckoning with our history can lead us to a better future, and that unless we acknowledge and learn from our past, we cannot move forward together. The future is not yet written. What happens next is up to us.

The UW–Madison Public History Project was made possible with support from the Office of the Chancellor using private funds.