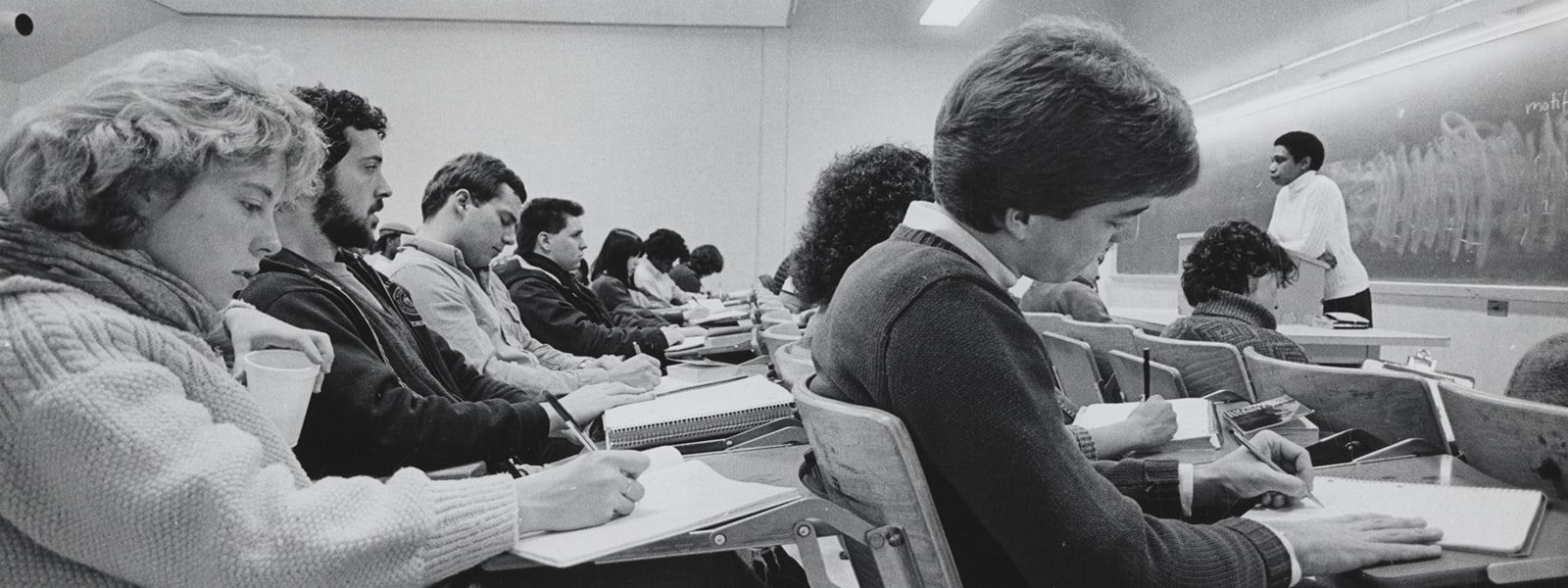

In the Classroom

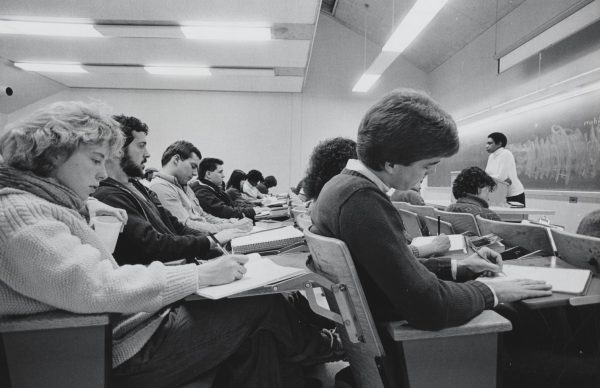

Education is at the heart of the university. It is the reason why UW–Madison was founded and why students of all backgrounds have long sought to attend it. UW–Madison has never had any formal discriminatory policies in admissions, but the white men who established the university did not truly create the university for all residents of the state. Ideas about who could attend—who was intelligent enough, who had the wealth and means to leave their jobs for the classroom, who was a citizen of the state—long defined who could gain admission to UW–Madison.

But getting in is only half the story. Once students from marginalized groups have arrived on campus, they have entered classrooms that have sometimes felt like hostile territory. They have fought to take their place among their classmates, to be treated with respect, and to learn about the topics that mattered to them from faculty who treated them like they belonged.

“Human defectives should no longer be allowed to propagate the race.”

Eugenics

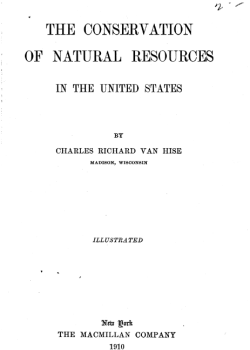

Some of the earliest students from marginalized backgrounds at the UW faced not just cultural prejudice but also academic research and curricula that purported to provide a “scientific” justification for discrimination against them.

Building off of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), the eugenics movement posited that “undesirable” human traits could be selectively bred out of the human gene pool. Successful experimentations in animal breeding were seen as proof that human genetics could also be controlled. Eugenic ideas targeted marginalized peoples — those with disabilities, those experiencing poverty, those accused of crimes — and relied on dehumanizing stereotypes and rhetoric. The UW proliferated these harmful ideas in annual eugenics courses. Notable UW–Madison figures such as President Charles Van Hise, sociologist Edward Alsworth Ross, and geneticist Leon Cole were proponents of eugenics. They used their academic credibility to further eugenic legislation in Wisconsin, including supporting a 1913 law that allowed for the forced sterilization of “defectives.” More than 1,800 people were forcibly sterilized in Wisconsin—the 11th most among states. The law was not removed from the books until 1978.

Download and view the full document “The Conservation of Natural Resources in the United States” (PDF)

Japanese American Students at UW

On February 19, 1942, two months after the Japanese Empire attacked Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The order authorized the forced evacuation and incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, many of them U.S.-born citizens. For those who were attending college or hoped to in the future, they found their educational goals put on hold.

Amid a national climate of fear and anti-Japanese racism, the UW–Madison community wrestled with how far to go in providing a home for Japanese American students. Many UW–Madison professors and students fought to allow Japanese American students to be admitted to the university. Administrators hesitated, fearing that if they moved too quickly without federal approval, they would lose crucial federal funding. While UW President Clarence Dykstra privately lobbied the federal government to create a comprehensive policy for admitting Japanese American students, very few were admitted during the war years.

Imagine the anxiety of college students in the middle of their spring classes. Would they be able to finish their courses and get credit for the semester? Should they forget the tuition they had paid, drop out in mid-March, and move to another state? Could they transfer to another university in only a couple of weeks to continue their education? Should they return to their parents so the family could stay together no matter what incarceration might bring?

Toshi Toki

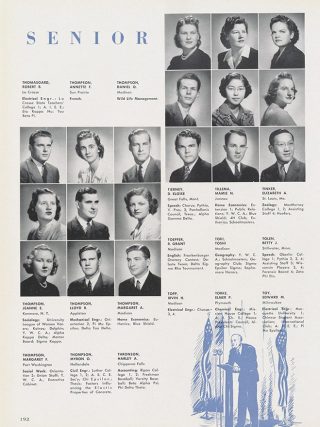

Before the beginning of WWII, only one Japanese American family lived in the Madison area—the Tokis. After graduating in spring 1942, Toshi Toki became a UW graduate student and teaching assistant in the geography department. As more Japanese American students and families began to move to Madison, the Toki household became a social hub for these new residents. After graduating with her master’s degree in geography, Toki moved to Washington, DC, to work for the U.S. Census Bureau.

Toru Iura

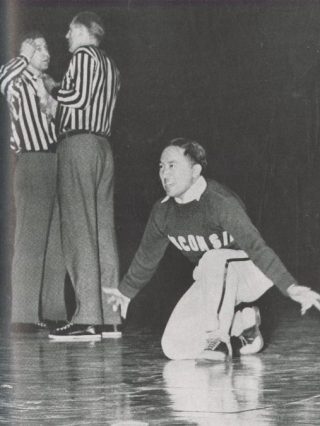

Toru Iura applied to UW–Madison in 1942. His family had left California earlier that year under a short-lived policy that allowed some Japanese Americans to “voluntarily evacuate,” leaving their lives and possessions behind. Iura loved his years at the UW, and he flourished in the field of mechanical engineering. By his second year of college, he was a member of multiple honor societies, served as business manager of the Wisconsin Engineer magazine, and worked at the Rathskeller. Iura embraced campus social life. He earned a position on the varsity cheerleading squad, a role he would encore at UW reunions for decades afterward. Iura graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1948. He then returned to California for his graduate studies and worked in space and missile development.

Hmong in Wisconsin

The HMoob (or Hmong) have a long history of demonstrating resilience when faced with displacement and marginalization by imperial powers. The HMoob originated in central China but were forced to flee to the mountainous regions in Southeast Asia (Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar) after a series of conflicts with Chinese authorities in the 19th century. Through this migration, the HMoob maintained their autonomy and their distinct culture, language, dress, and religion. In the 1960s, the HMoob allied with the U.S. CIA during the Secret War in Laos but were later persecuted by the victorious communist governments of Laos and Vietnam following the U.S. defeat. As a result, thousands of HMoob fled to Thailand by crossing the Mekong River. From the late 1970’s to early 2000’s, waves of HMoob refugees were resettled to third party countries, including the United States.

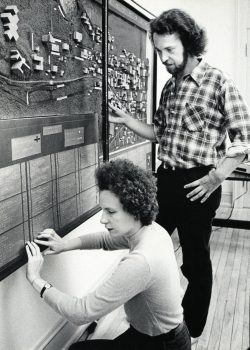

This wall-sized HMoob paj ntaub, which roughly translates to “story cloth,” documents the journey of the HMoob from war-torn Laos to the refugee camps in Thailand and, finally, to the United States. It was unveiled at the UW Multicultural Student Center’s 20th anniversary in 2008. With more than 58,000 HMoob living in Wisconsin, they are the state’s largest Asian American population.

Beginning in 2016, a group of HMoob American students formed an activist group — the HMoob American Studies Committee (HMASC) — to fight the racism they saw on campus, support HMoob students, and advocate for a HMoob studies program at UW–Madison. In 2018, HMASC partnered with educational researchers at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research to conduct research that would gain a better understanding of the experiences of HMoob students on campus. Together they created “Our HMoob American College Paj Ntaub,” a student-led research project to document the sociocultural and institutional factors that impact HMoob American student experiences at UW–Madison. The College Paj Ntaub research team examines how HMoob American undergraduates are sewing their own history through higher education as a symbolic way to continue the art form of a HMoob paj ntaub. Rather than a physical story cloth, “Our HMoob American College Paj Ntaub” draws on the lived experiences of HMoob American college students to expand on the themes of trauma, resilience, displacement, and diaspora.

Through their qualitative research study, the College Paj Ntaub team interviewed over 100 current and former HMoob students and found serious issues of exclusion and racism for HMoob students on campus. Participants reported avoiding certain academic buildings, residential halls, and Langdon Street because of the hostile environment, where verbal slights and indignities are commonplace. In contrast, the spaces in which participants stated they felt most welcome were student support programs, race-specific student organizations, and HMoob-specific classes. The team also found persistent discrimination and ignorance concerning their ethnicity, which results in HMoob American students being tasked with educating their peers and professors about their HMoob identity. In addition to this, HMoob students were mistaken as Asian international students or other Asian American ethnic identities. When it came to their academic experiences, HMoob students faced barriers such as “weed out” courses and negative advising experiences that caused them to alter their academic pursuits or pushed them out of college completely. Lastly, during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the team found that many HMoob students faced anti-Asian racism on campus and that there was an increase in stress, financial, and social instability.

Through their qualitative research study, the College Paj Ntaub team interviewed over 100 current and former HMoob students and found serious issues of exclusion and racism for HMoob students on campus. Participants reported avoiding certain academic buildings, residential halls, and Langdon Street because of the hostile environment, where verbal slights and indignities are commonplace. In contrast, the spaces in which participants stated they felt most welcome were student support programs, race-specific student organizations, and HMoob-specific classes. The team also found persistent discrimination and ignorance concerning their ethnicity, which results in HMoob American students being tasked with educating their peers and professors about their HMoob identity. In addition to this, HMoob students were mistaken as Asian international students or other Asian American ethnic identities. When it came to their academic experiences, HMoob students faced barriers such as “weed out” courses and negative advising experiences that caused them to alter their academic pursuits or pushed them out of college completely. Lastly, during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the team found that many HMoob students faced anti-Asian racism on campus and that there was an increase in stress, financial, and social instability.

HMASC and the College Paj Ntaub team have worked to share these results with the broader community and translate research findings into actionable change. For example, because of this research, HMASC was able to work with the UW–Madison Asian American Studies Program to establish a HMoob American Studies emphasis. The College Paj Ntaub team were also the first researchers to examine disaggregated institutional data on HMoob American students in the UW system, and make this data public for the first time in 2019, which exposed the educational struggles and challenges that HMoob students face at UW–Madison and across the UW System of public universities.

In 2022, in their fourth year together, the College Paj Ntaub team continues to advance their work by expanding their investigation beyond UW–Madison to both survey and interview HMoob American undergraduates across the UW system.

Members (current and former) of UW–Madison’s College Paj Ntaub team include (in alphabetical order):

Chundou Her

Lena Lee

Stacey Lee

Payeng Moua

Bailey Smolarek

Ariana Thao

Janessa Thao

Myxee Thao

Kia Vang

Mai Neng Vang

Matthew Wolfgram

Choua Xiong

Odyssey Xiong

Pheechai Xiong

Pa Kou Xiong

Pangzoo Lee

Madison Xiong

Ying Yang Youa Xiong

Chee Meng Xiong

Mai Chong Yang

Lisa Yang

Disability in the Classroom

“The only special efforts I would like to see the university make … is in accessibility in order to put us in the room and on equal ground with other students.”

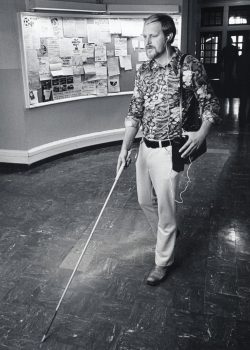

Students with disabilities have long lobbied for campus accessibility—for a campus where students with disabilities can perform the same tasks, achieve the same goals, and participate independently without the assistance of another person or an accommodation.

Students with disabilities have long lobbied for campus accessibility—for a campus where students with disabilities can perform the same tasks, achieve the same goals, and participate independently without the assistance of another person or an accommodation.

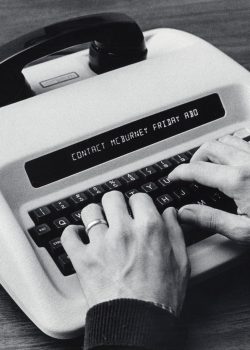

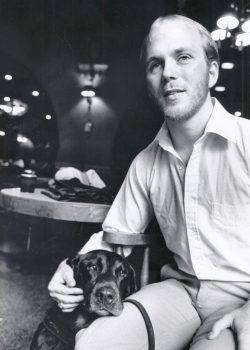

For decades, students with disabilities at UW–Madison succeeded despite the university’s disregard for accessibility. Arthur J. Petrie, the first known disabled student on campus, was forced to listen for lulls in traffic when waiting to cross busy streets. Petrie, along with others, personally paid classmates to assist them in taking class notes or reading materials aloud. Beyond the lack of classroom accommodations, students with disabilities were forced to navigate a physically unwelcoming campus. One student who used a wheelchair struggled to access classroom buildings without curb cuts. He recalled being told by UW–Madison admissions staff “to go to a flat-campus school.”

Founding of the McBurney Disability Resource Center

In the 1960s, Floyd Michael McBurney attended UW–Madison for both his undergraduate and law degrees. As a teenager, McBurney severely injured his spinal cord in an accident that led him to be paralyzed for the remainder of his life. At UW–Madison, McBurney faced many physical and social challenges, especially regarding the physical accessibility of campus while using his wheelchair. His professor James Graaskamp, who also used a wheelchair, connected with McBurney during his time on campus.

Following the death of McBurney in 1967, Graaskamp considered ways for the university to better support students with disabilities on campus. Inspired by McBurney’s perseverance and contributions to the Madison community, and in conjunction with the McBurney family, Grasskamp raised funds on behalf of his former student and used the money to create a disability service center on campus in his memory in 1977. The McBurney Disability Resource Center offers academic support so that the pursuit of knowledge is not hindered by the inaccessibility of campus. Graaskamp believed in a fully rounded experience for everyone in the UW–Madison community and also fought for accommodations in social, recreational, and athletic events.

Since the center’s opening, students with disabilities have pushed the university to provide more than accommodations. The McBurney Center now serves more than 3,000 students annually and has been integral in providing support for students with disabilities. Students and staff have continued to lobby for expanded support, including increased staffing and counseling services. The center’s ability to serve students is often limited by funding issues.

Accessing the Classroom

Students with disabilities have voiced concerns to university administrators over the inaccessibility of campus buildings and classroom spaces at UW–Madison for decades. In 1989, a campus accessibility survey conducted by student Marcia Carlson showed that only 25 percent of buildings and 10 percent of restrooms on campus were physically accessible. Without the proper physical accommodations, students with disabilities were often excluded from being able to be present and active in class. This created a barrier not only in students’ learning, but also in students’ opportunities to establish themselves within the intellectual communities on campus.

In 1994, law student Brigid McGuire contested the physical inaccessibility of UW classrooms. After an industrial accident that broke her back and caused chronic pain and impaired mobility, McGuire began using a motorized wheelchair device. Without proper accommodations, McGuire found it difficult to be physically present in class with her peers. On September 7, 1994, McGuire took a circular saw and removed a portion of a desk to create room for her motorized wheelchair. To the applause of her fellow classmates, she said, “I’d like to take my place among you as your classmate.” Though McGuire took matters into her own hands to have space within her classroom, many students who need physical accommodations are often ignored or forgotten if the spaces in which learning takes place are inaccessible.

Access Denied: Brigid McGuire vs. the University of Wisconsin–Madison

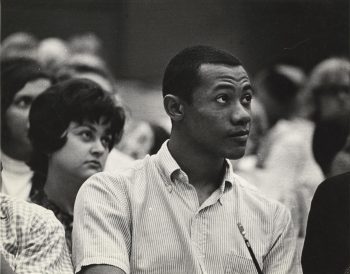

Racism in the Classroom

From the hard sciences and social sciences to the humanities, marginalized students at UW–Madison have confronted classroom spaces where they and their communities were the topics of study and debate. They are often in classrooms where the curriculum includes teaching white students about the lived experiences of people of color. Students of color often encounter careless, insensitive, and reductive approaches to teaching complex topics. Others feel singled out and asked to speak “for their entire race.” This has forced students of color into the uncomfortable position of challenging their professors and peers or remaining silent.

Oral Histories from the Classroom

“In several of my engineering classes, other students would greet me by speaking African American Vernacular English or with Madea (Tyler Perry’s Madea character) references. I gave them no indication whatsoever that is how I wanted to be greeted. Other persons have touched my hair without my permission.”

“In group settings, people avoid talking to you, making eye contact, or blatantly ignore you when talking about an activity or assignment related to class. Instructors that help other students more than they help you. Give longer, more in-depth evaluations to students they favor. Pass over you when having open class discussions.”

“To be a Black woman in STEM is a constant battle. … You’re always proving yourself.”

“White teachers don’t take me seriously even when I understand the content better than them.”

“It was a lot to deal with as a student. I was also in 18 credits at the time, trying to finish my senior year, and it was a point where nobody asked to be a student activist. And I think that’s also a toll that a lot of students of color face on campus is we’re not just students here. We don't have the privilege of just being students; we have to be students and educators a lot of the time too. We have to educate our teachers. We have to educate our peers. [That’s] a big load to carry when you’re also a student. But this was almost like having a full-time job and I already had two jobs that I was working at the time too. So just being able to balance all of it was difficult at times.”

“And most of the time, it feels like I was one of the only Black students in the room or lecture hall. There were maybe like 10 people of color and two Black students. So that was definitely a very isolating feeling especially when it came time to work with other people or talk to those around you. I was just like, I really didn't feel welcomed. ... One of the silver linings was that I really built strong relationships with the other Black students.”

“I was in a sociology class, and we were talking about race one day and you could just—there were like five people of color in that class—you just could hear the white kids moan. … Those are the constant things that they don’t recognize because they’re the majority. … You become hyper aware to all these little things. It’s just a lot and it eats away at you every time it happens.”

“Professors mostly; one has commented on how articulate I am. Another professor accused me of plagiarism (when I didn’t) because she didn’t think I had the capabilities to write well.”

“I could go days without seeing other Black people.”

Studies show that these experiences transcend the anecdotal. The 2016 Campus Climate Survey Report concluded that “students belonging to historically underrepresented and disadvantaged groups reported less positive feelings and experiences.” It also showed students of color, LGBTQ students, students with a disability, and trans/nonbinary students were two to three times more likely to report experiencing incidents of hostile, harassing, or intimidating behavior directed at them personally.

These alienating experiences extend far beyond the classroom. In 2015, in response to a student question about the impact of alcohol culture on students of color, the first Color of Drinking study was administered and led by Reonda Washington of University Health Services. The Color of Drinking study in 2018 found that “African American/Black students consider leaving UW–Madison at three times the rate of white students” and “cited the racial climate as the number one reason.” It also stated that “approximately 62 percent of students of color experience microaggressions at UW–Madison.”

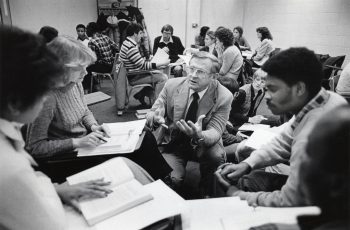

Faculty and Staff

“You see the Negro students on campus, but where are the Negro professors at this university? If this university wanted qualified Negroes on the faculty they could find them. Now there’s just a lot of pious talk—no action.”

What happens in the classroom is impossible to separate from the work of educators. For its first 100 years, UW–Madison had very few faculty or staff from marginalized communities. Most served in nontenured positions or as visiting lecturers. Regardless of position, they earned lower pay, often experienced hostile working environments, and faced difficulties finding housing. They often found themselves without community. Meanwhile, students from marginalized groups had only very limited opportunities to learn from these scholars. They found themselves without mentors whom they could connect with and who understood firsthand the obstacles they faced.

Academic life is not just inside the classroom. The faculty and staff who make the university work are not just teachers. There are many other stories to be told about the struggle for equity and inclusion in research, scholarship, and other forms of academic labor.

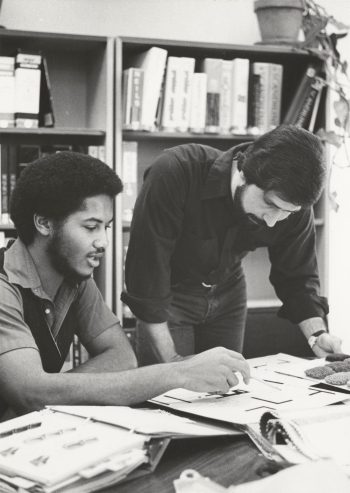

Ethnic Studies at UW–Madison

“We exist because students, faculty, and staff demand it.”

Ethnic studies programs at UW–Madison were founded in response to the demands of marginalized students, faculty, and staff. The programs were meant to meet the unique needs of students of color on campus and to assist in educating the larger campus community about ethnic cultures and identities. Students fought to establish classes on how minoritized people shaped this nation through science, art, literature, and history. Students of color also sought classrooms where there was already a shared understanding about the experiences of nonwhite people. Though these programs have provided a vital academic space for marginalized students, faculty, and staff, they have faced significant challenges—both at the time of their formation and today.

The ethnic studies units continue to listen to and learn from students and have taken deliberate action to work together. Recently the units have revived a comparative ethnic studies course, which rotates among the units.

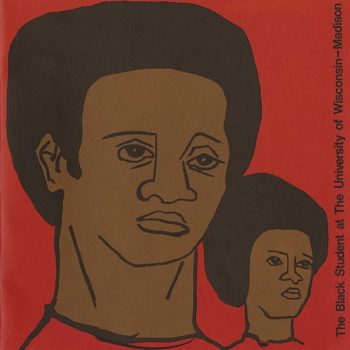

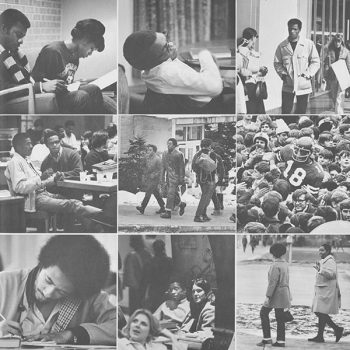

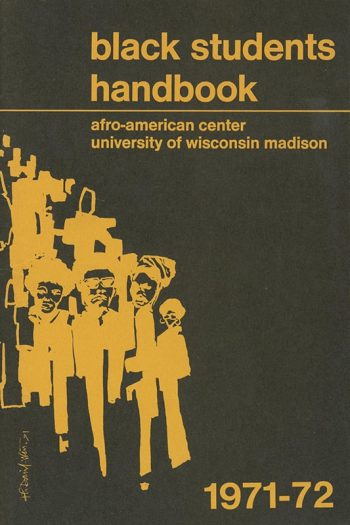

The Afro-American Studies Department

As the Black Power movement gained momentum during the late 1960s, students at UW–Madison joined their peers across the nation in organizing against racial injustices—especially in education. In 1969, Black students at UW–Madison became increasingly unsettled by rampant racism and the inattention to the experiences of Black students. The 1969 Black Student Strike followed. The students on strike made their return to the classroom contingent upon the university meeting 13 demands. Among those was the creation of a department of Black studies. Students—both Black and non-Black—challenged the university to acknowledge the academic value and rigor of Black studies. Students cited the importance of Black intellectual thought, taught by Black faculty, as a reason for the department’s necessity. Students across campus protested until the university finally granted approval on March 3, 1969, for what is now the Department of Afro-American Studies.

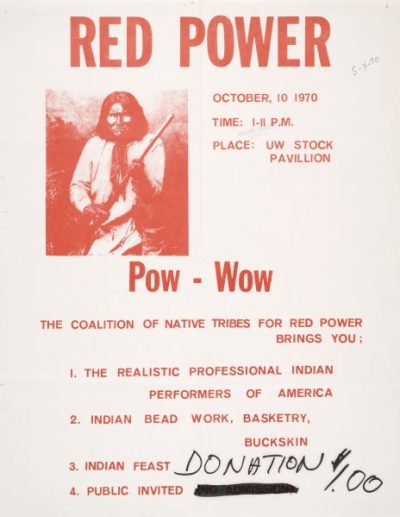

The American Indian Studies Program

At the high point of the Red Power Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, Native students at UW–Madison formed the Coalition of Native Tribes for Red Power (CNTRP), which later became Wunk Sheek. In 1968, with community support, the CNTRP challenged the university to acknowledge the importance of their histories, cultures, and languages. In 1970, the CNTRP sent four demands to the university, including recruitment of and funding for Native students. In response, the university formed an ad-hoc committee dedicated to addressing these concerns. The committee proposed five recommendations to better the university’s commitment to Native students and studies, including the establishment of a department of American Indian studies. Chancellor Edwin Young endorsed the report in 1971. Though the committee called for a full department, the American Indian Studies Program was formed in 1972. It is celebrating its 50th anniversary this fall.

The choice to create a program versus a department was not without consequence. Departments, not programs, serve as tenure homes for faculty and organize most major programs. Despite funding not being guaranteed for either departments or programs, ethnic studies programs at the university have been consistently threatened by state budget crises and competing strategic demands.

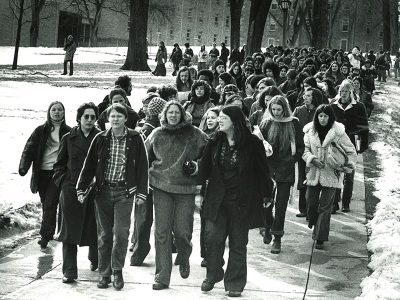

The Chican@ & Latin@ Studies Program

Much like other ethnic studies programs, the Chicano Studies Program was born out of student-led activism. Latinx students recognized a lack of courses and faculty that specialized in Chicano history, culture, and intellectualism. In 1974, student activists with MEChA, sensing resistance within the university, lobbied the state legislature to establish a Chicano studies department. After months of continuous protests on campus and in Madison at large, the legislature agreed and the university established a program in the School of Education with minimal funding. MEChA continued to urge the university to inaugurate a full department, not a program, citing that Chicano studies as it stood lacked the economic vitality to fully serve students and faculty. Though internal conflict surrounding the core values and purposes of the Chicano Studies Program kept activists and academics at odds, there remained one common goal: establishing Chicano studies at UW–Madison. Today’s Chican@ & Latin@ Studies Program is still not recognized or funded as a department despite its academic rigor and popularity among students.

The Asian American Studies Program

In the 1980s, UW–Madison’s campus experienced an uptick in racist acts. A notable instance was in spring 1987 when the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity hosted its annual “Fiji Island” party. A tradition of more than 40 years, the party featured students in grass skirts and full-body blackface. To decorate, they erected a racist statue of a dark-skinned caricature on their front lawn. Controversy erupted immediately. The fraternity, trying to minimize its actions, assured students that the caricature was not Black, but rather Filipino. Both Black and Asian American students worked together to organize a response. Days of protests ensued as students reacted to the racist actions of fraternities and the racism of the campus community at large.

In 1988, students formed the Asian Coalition, which challenged the institution to take a direct stand against anti-Asian racism. The coalition proposed that the university create an Asian American studies program to provide students with opportunities to learn about Asian American experiences, culture, and intellectual thought in a structured and rigorous academic environment. After continued lobbying by the coalition, the university created the first Asian American studies program in the Midwest in 1991. Besides offering a certificate in Asian American studies, the Asian American Studies Program today offers an emphasis in HMoob American Studies.

“You can never stop pushing or feel satisfied. There’s so much more work to do on this campus.”

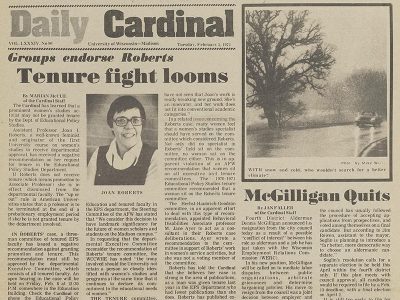

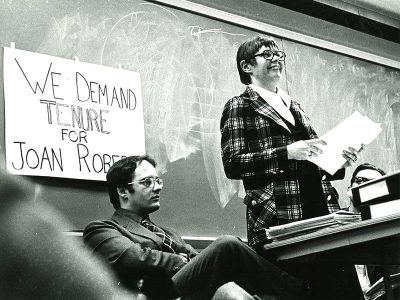

The Gender and Women’s Studies Department

In the 1970s, there was an increased interest in women’s studies at UW–Madison. Joan Roberts, a professor in the Department of Educational Policy Studies, was the only faculty member in her department to teach women’s studies. She was considered to be a key contributor to the intellectual study on women’s issues on campus and was strongly committed to her students. In 1974, Roberts was denied tenure by an all-male committee on the grounds that her intellectual work did not meet university standards. However, in the years prior, several male faculty members were granted tenure with less rigorous academic and service work than Roberts. Citing that her denial of tenure was based on gender discrimination, Roberts contested the decision with ample community support. Her tenure denial sparked controversy on campus. Protests ensued as Roberts battled her tenure case in court. She was eventually awarded an out-of-court settlement of $30,000.

After her tenure denial, Roberts argued that the UW’s handling of her case had larger implications for women on campus. In late 1974, in response to protest and outrage, the university moved to prove its commitment to women. The chancellor’s Committee on Women’s Studies researched programs across the nation in preparation to establish one at UW–Madison. The Women’s Studies Program was founded in 1975, and it became a full department in 2008.

“Women are determined to continue to foment rebellion until they finally bring about equality for women, inside and outside the hallowed halls of academia.”

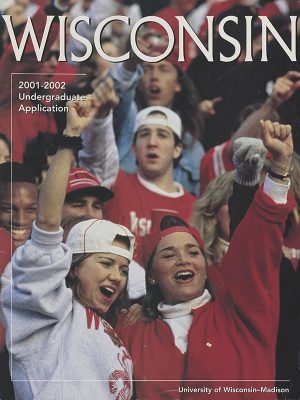

Who Belongs?

There is a tension between the aspirations for diversity on campus and the reality of it at primarily white institutions. This can be most apparent in university recruitment and advertising materials. UW–Madison has long touted its commitment to diversifying the campus community. Yet, as the campus has marginally grown more diverse, the university has often tried to promote an image of UW–Madison that’s more diverse than it truly is. This has left students and faculty of color feeling tokenized. Further, it has complicated the relationship that marginalized people want to have with the university. While they want to be represented as a part of the Wisconsin community, is this authentic representation? In the past 20 years, two major controversies have brought this tension to the forefront on campus.

“They got people of color to come here but they didn’t make it a welcoming place for us to want to stay here.”

Admissions Brochure

“Universities have a responsibility to portray diversity on campus, and to portray the type of diversity that they would like to create. It shows what their value systems are. At the same time, I think they have a responsibility to be actively engaged in creating that diversity on campus that goes deeper than just what’s in the picture.”

In 2000 Diallo Shabazz, a Black student and staff member of the Multicultural Student Center (MSC), discovered a photo of himself on the front page of the annual admissions brochure, smiling in the crowd at a UW football game. Shabazz immediately knew something was wrong. He had never attended a football game. Administrators from the Office of Admissions and Recruitment doctored the photo to include Shabazz and make the crowd look more diverse. Shabazz noted that the admissions office was merely two stories up in the same building where he worked.

The controversy garnered national attention and prompted students on campus to organize and call out the university’s “lack of understanding of diversity.” Students of color were quick to note that the UW’s image of itself as a diverse university did not match the experiences of students on campus.

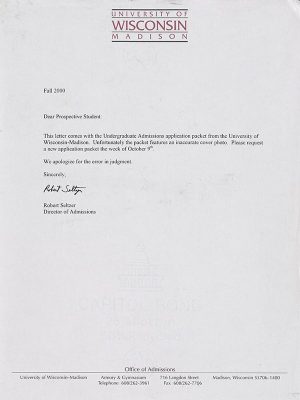

Admissions Director Rob Seltzer, who approved altering the photo, and Al Friedman, director of University Publications, publicly apologized to Shabazz and the UW community. Paul Barrows, vice chancellor of student affairs, called it an “error of judgment.” Barrows revealed it was vital for the university to address the faked admissions packets quickly “because we are in the heat of a very competitive admissions cycle and I don’t want to lose any time.” University spokesperson Patrick Strickler said that all 110,000 brochures would be reprinted with a different cover that would no longer display Shabazz.

Homecoming Video

In 2019, the UW–Madison Homecoming Committee, a student organization sponsored by the Wisconsin Foundation and Alumni Association, released a promotional video for Homecoming that featured students celebrating the UW. Yet, virtually every student was white. Payton Wade, a member of the historically Black sorority Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., brought attention to the fact that Black students were filmed but the footage wasn’t used in the video. The backlash was immediate. The video was titled “Home Is Where WI Are.” In response, students of color created a video titled “Home Is Where WI Aren’t” and protested across campus. The Homecoming video was the central inspiration for the creation of the Student Inclusion Coalition (SIC).

Sources

- Van Hise, Charles R. The Conservation of Natural Resources in the United States. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1918.

- Goldberg, Chad Alan. Education for Democracy: Renewing the Wisconsin Idea. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2020.

- The University of Wisconsin Catalogue. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1935–36.

- Kaelber, Lutz. “Eugenics in Wisconsin.”

- Paul, Julius. “‘Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough’: State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice.” Washington, D.C.: Private collection of the Walter Reed Institute of Research, 1965.

- Goc, Michael, ed. Island of Refuge: Northern Wisconsin Center for the Developmentally Disabled, 1897–1997. Friendship, WI: New Past Press, 1997.

- University of Wisconsin–Madison, Badger Yearbook Vol. 57 (1942).

- Takahashi, Rita. “Toru Iura Paper,” Attachment to Letter to Toru Iura, Box 43, Folder 3, 25 November 1998, Japanese Student Evacuee Files – President’s Records 1888–1971, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Zimmerman, Mae E. “New Staff.” Wisconsin Engineer, September 1944.

- Wendt, Kurt F. Letter of Recommendation to Officer in Charge on A.S.T.P. Board, 23 January 1945, Japanese Student Evacuee Files – Clarence Dykstra Files, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Vue, Mai Zong. Hmong in Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2020.

- Smolarek, Bailey and et al. HMoob American Undergraduate Students at University of Wisconsin’s 4-Year Comprehensive Colleges – Background, Enrollment Statistics, and Graduation Trends (PDF) Center for Research on College-Workforce Transitions, UW–Madison.

- Jacobs, Irene D. “Campus Concern: the Disabled Student.” Wisconsin Alumnus Magazine, March 1973.

- “Blind U.W. Student Takes Notes, Typewrites, Finds Way Without Assistance.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), May 31, 1924.

- Gutknecht, Karl S. and Tom Menzel. “No Longer is UW Mt. Everest for the Physically Handicapped.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), Mar. 10, 1972, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Who was the McBurney Center named after?” Ask Flamingle (blog),Wisconsin Foundation and Alumni Association.

- Trueba, Cathy. “UW–Madison: Ceremony to dedicate new McBurney Disability Resource Center at UW–Madison.” WisBusiness, Last modified March 29, 2011.

- “About.” McBurney Disability Resource Center website.

- Wathen, Emma. “Access Denied: Brigid McGuire vs. the University of Wisconsin–Madison.” UW–Madison Public History Project (blog), April 1, 2020.

- Hill, Morgan. Interview by Angelica Euseary. 9 March 2021, virtual interview, UW–Madison Public History Project, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries, Madison, WI. Digital audio file.

- Ibrahim, Ahmed. Interview by Angelica Euseary, 22 September 2020, virtual interview, UW–Madison Public History Project, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries, Madison, WI. Digital audio file.

- Long, Harvey. Interview by Angelica Euseary, 14 September 2020, virtual interview, UW–Madison Public History Project, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries, Madison, WI. Digital audio file.

- Wade, Payton. Interview by Taylor L. Bailey, 21 March 2022, virtual interview, UW–Madison Public History Project, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries, Madison, WI. Digital audio file.

- Washington, Reonda and et al. “The Color of Drinking: An exploratory study of the impact of UW–Madison’s alcohol culture on students of color.” (PDF) University Health Services, UW–Madison.

- “Color of Drinking.” University Health Services.

- Smoller, Jeff. “Barbee Laments University; Says Equality is Just Talk.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Dec. 13, 1963, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Cohan, Dustin. “Surviving Conditions and Competing Visions: The Fight for a Chicano Studies Department.” UW–Madison Public History Project (blog), October 5, 2020.

- Bohanon, Mariah. “African American History: A Look Back at Early Student Activism.” Last modified December 19, 2019.

- Greenberg, Peter, Ron Legro, and Judy Shockley. “Blacks Demand Reform, Students Stop Classes.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Feb. 8, 1969, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Thirteen Needs Explained,” Box 13, Folder 1, Afro-American & Race Relations Files, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Cardinal Staff Writers. “Student Organizations Meet to Support Strike, TAA to Walk-out, Teach.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Feb. 12, 1969, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Report of Committee on Studies and Instruction in Race Relations,” Faculty Document 260, March 3, 1969, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “A Challenge to the University of Wisconsin,” Box 57, Indians Folder, September 25, 1970, Coalition of Native Tribes for Red Power (CNTRP), Native American Files, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Memo from Edwin Young to the Ad Hoc Committee on Native American Programs, June 16, 1971, Box 57, Folder Indians, Native American, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “Young Approves Indian Studies.” Wisconsin State Journal, July 10, 1971.

- Laws of Wisconsin 1975, 30 July 1975, Box 1, Chapter 39, Chican@ and Latin@ Studies Archives, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- “UW–Madison Okays Chicano Studies Program.” Janesville Gazette, Aug. 13, 1975.

- Castañeda, Tony. Interviewed by Dustin Cohan. March 6, 2020, virtual interview. Audio recording. UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries, Madison, WI.

- Choy, Peggy. Interviewed by Dustin Cohan, May 4, 2020, virtual interview. Audio recording. UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries, Madison, WI.

- Worthington, Rogers. “‘60s Style Revival on Racism Gets Revival at U. of Wisconsin.” Chicago Tribune, Nov. 12, 1987.

- “UW Disciplines Fraternity For Party.” AP News, May 15, 1987.

- Voice of the People, “Filipino groups protest frat racism.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), May 15, 1987. https://newspaperarchive.com/madison-capital-times-may-15-1987-p-13/.

- Reinke, Robert “Asian studies program to be proposed at UW.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Nov. 22, 1988, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Schmeling, Sharon L. “Asian American Studies?” Capital Times, (Madison, WI), Nov. 29, 1988.

- Lee, Sharon S. “Building Asian American and Ethnic Studies in the Midwest.” Last modified in 2012.

- Roberts, Joan. Creating a Facade of Change, Informal Mechanisms Used to Impede the Changing Status of Women in Academe. Pittsburgh: KNOW, 1975.

- Sherman, Diane. “Tenure Denial Seen As UW Commitment Test.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), Feb. 6, 1974.

- McCue, Marian. “Groups endorse Roberts: Tenure fight looms.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Feb. 5, 1974, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Welter, John. “Joan Roberts Hasn’t Dropped UW Tenure Fight.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), Jan. 17, 1976.

- Hesselberg, George. “Tenure Denial Spurs Hassle.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), Feb. 28, 1974.

- “U prof awarded $30,000 in tenure battle.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Mar. 8, 1979, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- McCue, Marian. “Firing sparks controversy.” Daily Cardinal (Madison, WI), Feb. 12, 1974, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Beckmann, Anne. “New staff opening in Women’s Studies.” Capital Times (Madison, WI), Nov. 22, 1974.

- Bennett, Julianna. Interview by Angelica Euseary, 15 April 2021, virtual interview, UW–Madison Public History Project, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries, Madison, WI. Digital audio file.

- Prichep, Deena. “A Campus More Colorful Than Reality: Beware That College Brochure.” National Public Radio, Last modified December 29, 2013.

- “Signed Student petitions” Box 3, Multicultural Student Center Records 1988–2018, UW–Madison Archives, UW–Madison Libraries.

- Claiborne, William. “Black-White Issue Leaves University Red-Faced; Brochure Photo altered to Illustrate Diversity.” Washington Post, Sept. 21, 2000.

- “University Red-Faced Over Diversity Fabrication.” Chicago Tribune, Sept. 21 2000.

- Chappell, Robert. ““Home is Where We Aren’t.’ Homecoming Promo Video Sparks Backlash as Black Students are Cut Out.” Madison 365, October 2, 2019.

- Baldassano, Ariana. “‘Home is Where WI Aren’t: New video from Student Inclusion Coalition.” Channel 3000, Last modified August 31, 2021.

In conclusion

“True resistance begins with people confronting pain … and wanting to do something to change it.”

As we fearlessly sift and winnow through the university’s past, many hard truths emerge. We also find hope, and the ever-present possibility of change for the better. The university has changed in many ways across its history, often because members of the campus community have demanded it.

We believe that reckoning with our history can lead us to a better future, and that unless we acknowledge and learn from our past, we cannot move forward together. The future is not yet written. What happens next is up to us.

The UW–Madison Public History Project was made possible with support from the Office of the Chancellor using private funds.