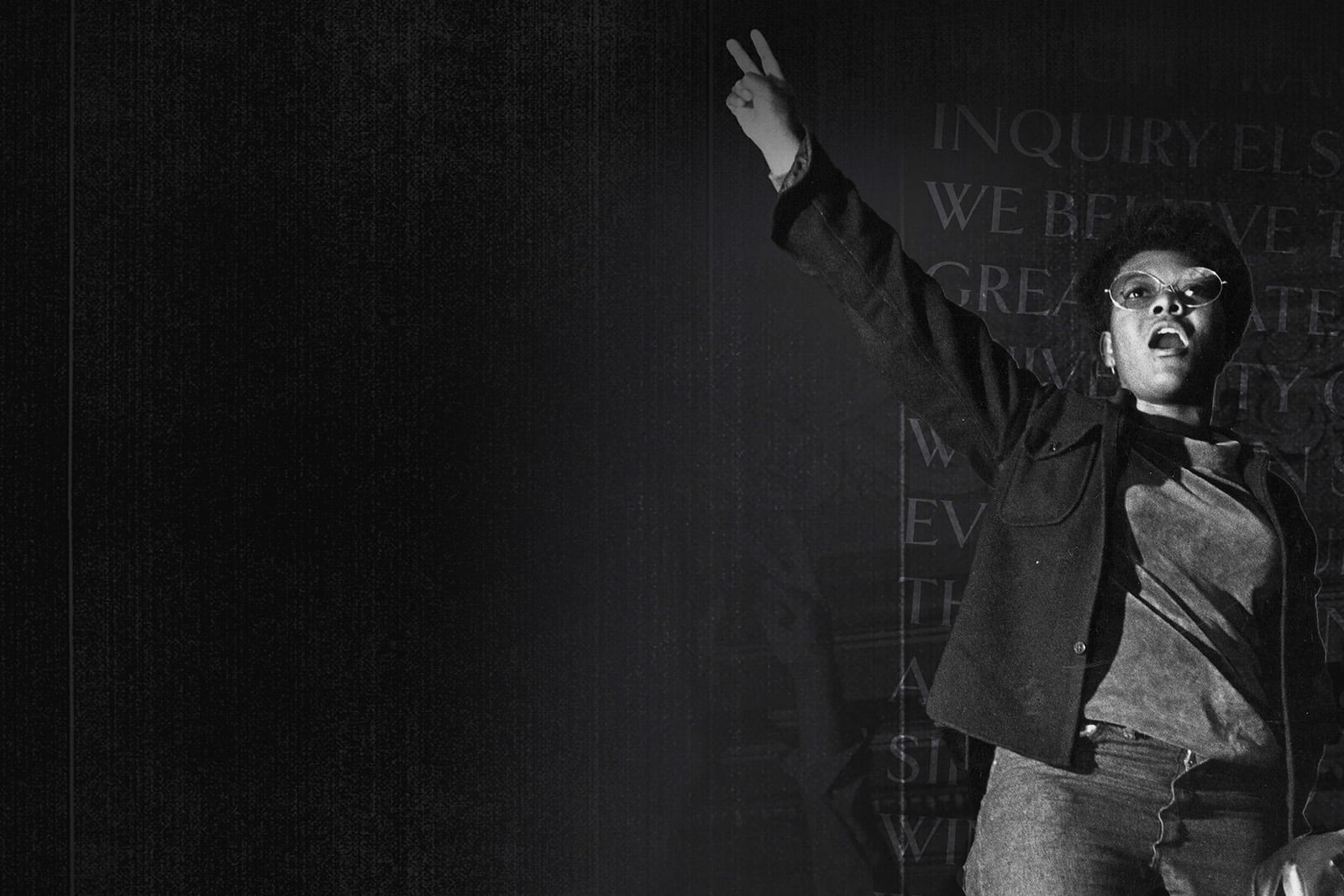

UW–Madison’s history of exclusion and resistance

In August 2017, the white supremacist rally and fatal car attack in Charlottesville, Virginia, jolted the nation and our campus. In the wake of that tragedy, UW Chancellor Rebecca Blank commissioned a study group to research two student organizations from the 1920s with the Ku Klux Klan name. The resulting report recommended further efforts to not only confront the university’s history of exclusion, but also highlight the contributions of marginalized people who pushed back. The Public History Project was born in 2019, and its work has culminated in a fall 2022 exhibition at the Chazen Museum of Art and the digital version before you.

In conclusion

“True resistance begins with people confronting pain … and wanting to do something to change it.”

As we fearlessly sift and winnow through the university’s past, many hard truths emerge. We also find hope, and the ever-present possibility of change for the better. The university has changed in many ways across its history, often because members of the campus community have demanded it.

We believe that reckoning with our history can lead us to a better future, and that unless we acknowledge and learn from our past, we cannot move forward together. The future is not yet written. What happens next is up to us.

The UW–Madison Public History Project was made possible with support from the Office of the Chancellor using private funds.